Words and Photos: Indi Blake

Two hours south of Mexico’s capital, beneath the shadow of a massive volcano, lies the bustling cosmopolitan city of Puebla. The city, which is known for its stunning colonial architecture and world-class gastronomy, is the fourth largest in Mexico and attracts thousands of visitors each year. Unbeknownst to many of those on the streets above, a network of tunnels extends underground beneath their feet, kept secret for hundreds of years. The tunnels, some as large as 15 feet wide, were originally created for water diversion but, over their long history, have been co-opted for use in smuggling, war and escape from persecution. Their recent rediscovery in 2015 has allowed historians to peer back at the roughly 500 years of Mexican history left behind in the relics and stories preserved within the tunnel network.

For years before their existence was confirmed by historians, locals in the area had exchanged whispers about secret tunnels that ran under the city. Largely dismissed as exaggerated urban legends, these stories described a tunnel network known only to a select few. In 2015, during an urban development project, workers digging under the city unexpectedly smashed through the walls of one such tunnel and, in doing so, inadvertently smashed a hundred years’ worth of archaeological and historical dogma. When initially discovered, the system of tunnels was thought to be nothing more than an old sewer system, but as crews began to excavate the cavity, the enormous size and scope of the tunnels became apparent.

Though the full extent of the tunnels under Puebla may not be known, at least 10 kilometers have been uncovered and mapped so far, all of which were likely constructed shortly after the founding of Puebla in 1531.

At the time of their rediscovery in 2015, much of the tunnel network had been clogged to the ceiling with mud for some time. Legends of the tunnels circulated by city goers likely originated long ago and were passed down by word of mouth from one generation to the next, even after the tunnels had become impassable. When they were eventually cleared, archaeologists discovered countless artifacts in the mud, representing the many historical milestones that occurred during the tunnel’s lifetime. Among them were weaponry and tools dating back to the Mexican liberation from Spain and the subsequent French invasion, as well as wagon wheels, children’s toys and cookware. By piecing together these bits of evidence, historians are able to create a series of snapshots that reveal a never-before-seen perspective of Mexican history.

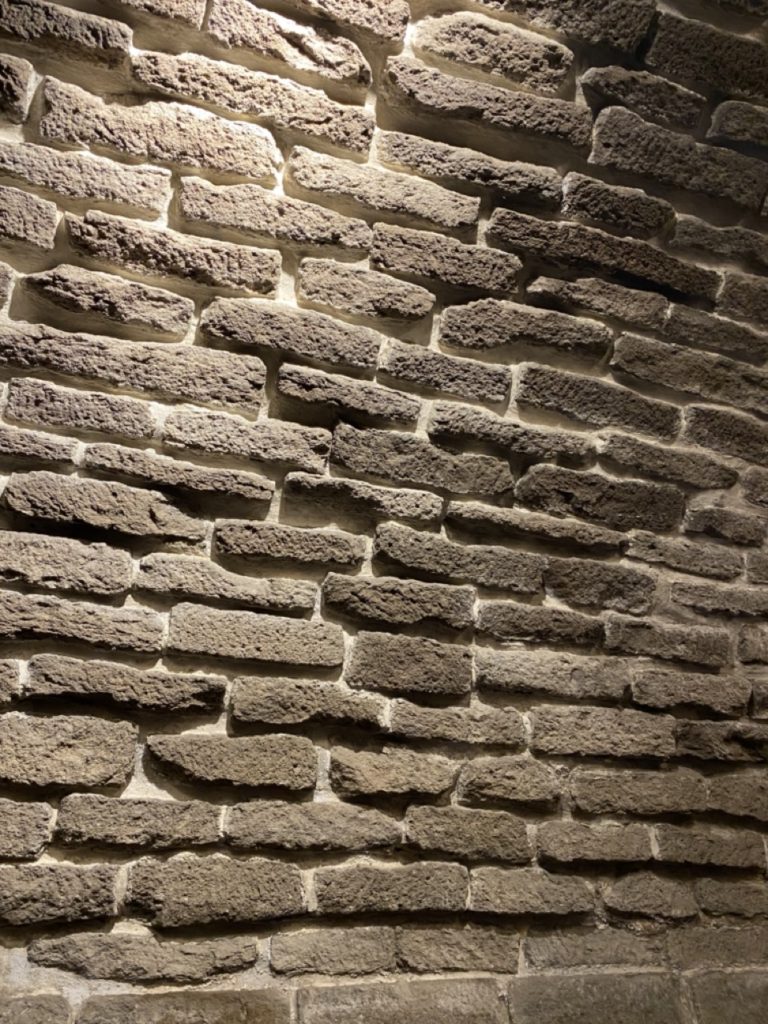

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish had established a permanent presence in Mexico. Their new capital, Mexico City, was the former site of a sprawling empire previously ruled over by the Mexica/Aztecs. To the southeast, on the Atlantic Coast, the Spanish established their main port city of Veracruz, which was separated from Mexico City by roughly 250 miles of mountains and jungles. The colonizers needed a stopover point to resupply and rest during trips back and forth to and from the capital. The city of Puebla was their solution. Founded in 1531, Puebla was abnormal in that it was not originally established by indigenous peoples like many of the other cities the Spanish were erecting around the country. This meant that city planners could design the layout from scratch. The river valley that the township was settled in was fertile and arable but also was prone to prevalent flooding that destroyed parts of the city in its early days. Puebla’s city planners included in their blueprints a series of aqueducts to better manage the water flowing through the valley and make it more readily available to its citizens. In order to accommodate significant flow, many of these tunnels were built to surprisingly large proportions using stacked brick and stone to line the walls of the semi-circular arched tunnels.

In addition to those that accommodated water, some tunnels connected important civic and religious buildings, such as the city’s cathedral and a military fort. These tunnels would have allowed users passage between parts of the city completely unnoticed. Their exact intended purpose is unknown, and interestingly, no official records of their construction or existence have been found, giving the tunnels an air of secrecy that has persisted since their creation.

There is evidence that the tunnels may have been used during the Spanish Inquisition as a means for certain groups to escape persecution. During the 16th-17th centuries, the Catholic Church in Spain extended its crackdown on heresy all the way to the Americas. During this time, groups accused of practicing other religions or worshiping indigenous gods were severely punished, with some even sentenced to burning at stake. Suspicion and fear may have led some clergy members to use the tunnels to escape if they harbored sympathies for the indigenous population or for other factions of the faith.

Roughly 40 years after Mexico had gained its independence from Spain in 1821, France invaded Mexico due to debt payments that active Mexican president Benito Juarez had put a hold on. When negotiations broke down, France attempted to take control of the country. Coming ashore in Veracruz, the French attempted the same march towards Mexico City as the Spanish did three hundred years before. Inevitably, the French campaign reached Puebla, where it was pushed back in a surprise defeat. The French Army’s weaponry was far superior to the Mexican Army’s outdated muskets, and their strict training made them a formidable force. Despite this, they suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retreat after the battle. The Mexican victory is still commemorated to this day as the holiday of Cinco de Mayo.

Ammunition, guns and gunpowder found in the Puebla tunnels that date from this time period hint that the Mexican army had a secret advantage during this battle. Stationed at the Loreto and Guadalupe forts, the Mexican military was able to transport weapons, food and supplies through the tunnel network, thereby fueling their defense indefinitely.

Though the military artifacts found in the tunnels mostly date to the mid-18th century, it is possible that the tunnels also played roles in the Mexican Wars of Independence before and Mexican Revolution many years later. Many of the other artifacts still remain a mystery. Why were there so many children’s toys and cookware found within the tunnels? It is possible that the tunnels were used as a refuge during violent battles, a place where sheltering families could feel safe. Perhaps the secrets of the tunnels had leaked to commoners who used them in their day-to-day lives. Archaeologists and historians are still trying to put together clues about the purposes these tunnels served over their history. If additional secret passages containing more evidence are discovered in the coming years, they could shed light on some of these unanswered questions.

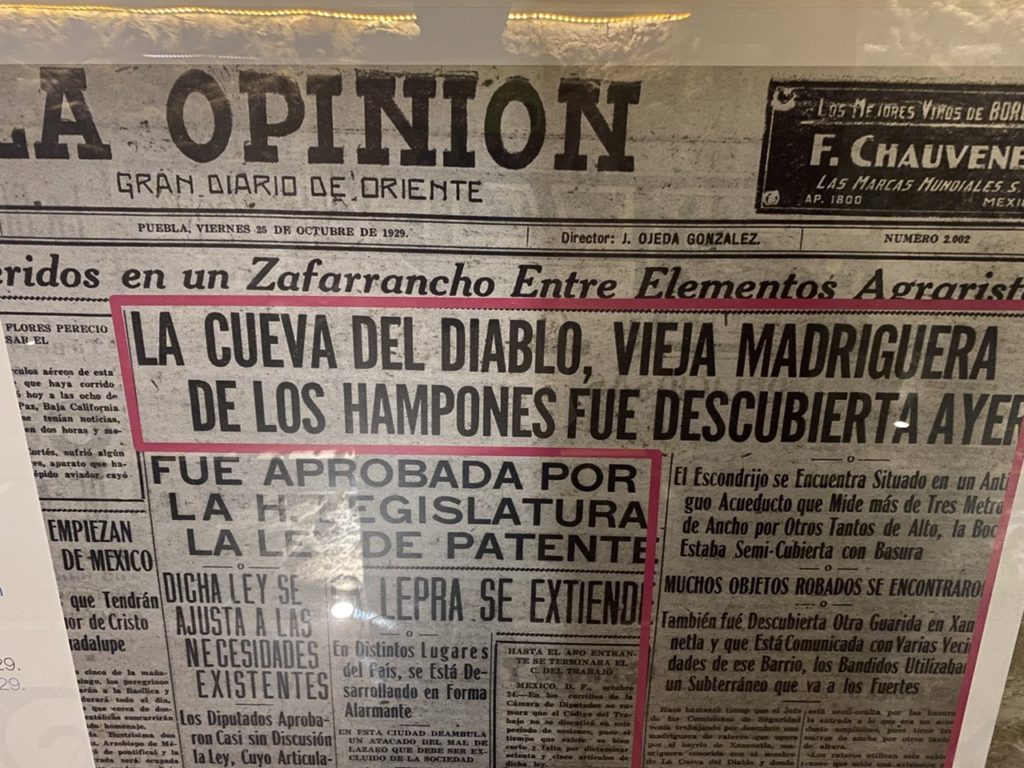

The next documented mention of the tunnels didn’t come until 1929 when a local newspaper publication reported on a peculiar passageway known to locals as “Cueva del Diablo” or “Devil’s Cave.” According to the document, the passageway was used by thieves to clandestinely transport and store large stolen objects.

In 1965 a historian named Enrique Cordero y Torres interviewed a number of locals claiming to have information about the tunnels. From his interviews, he created a map showcasing the most agreed-upon underground routes, many of which have been proven correct. Since then, the tunnels had largely been forgotten. Their lifetime of secrecy finally ended when the municipal workers in 2015 stumbled upon them. A year after their rediscovery, the city opened them to the public, allowing visitors to descend roughly 5 meters underground and imagine the many times the same tunnels were used over the years.

Today, the masonry walls of the ancient tunnels still hold strong. The structural curvature of their ceilings keeps the earth from collapsing around them. Though many sections have been reinforced with new mortar, the original brick and stone remain. Because brick was hard to produce and more expensive, most of the length of the tunnels feature stone in the walls and transition to brick in the ceiling. The brick pattern varies in different sections of the tunnel, creating a beautiful visual effect when looking down its length. The tunnels, kept in the dark for hundreds of years, are today outfitted with lights illuminating informational plaques recounting the bizarre story of their construction, abandonment, and later rediscovery. As the city has grown, large pipes have been added intersecting the tunnels at odd angles forcing visitors to duck their heads as they pass under them, juxtaposing the subterranean engineering of today’s world with that of the past. Many of the artifacts found during the tunnel’s excavation line its cavernous walls continuing their long tenure underground, though now under glass. Despite the exhibit being relatively new, it is gaining popularity and attracting both Mexican and international tourists alike.

In today’s world, details of nearly every decision city planners make are saved and cataloged. Civic engineers have essentially made it their goal to minimize surprises. The Puebla tunnels are proof that there are still ancient secrets and mysteries out there waiting to be rediscovered. Such discoveries have the potential to transform our previous understanding and add nuance to long-held historical paradigms.