Words & Images: David H. Glabe, P.E., Director of SAIA

This could be a difficult question to answer, particularly if you don’t know scaffolding! It’s one of those classic situations of not knowing what you don’t know and thinking that you know what you know. Did you follow that?

Scaffolding is essential equipment for masons, as you well know. Masons cannot accomplish their work without some type of temporary elevated platform so that masonry structures can be constructed. In fact, masons have been successfully using scaffolding for centuries. Unfortunately, scaffolding has been used unsuccessfully on more than a few occasions, leading to injuries, deaths, bankruptcy, fines and lawsuits. So, what’s the problem? Is it due to poor equipment, improper scaffold installation, careless use, lousy attitudes, or—all the above? Statistics show that scaffold accidents are typically due to either poor construction or poor use. To avoid a calamity on your jobsite, here are a few things to look for.

Training: You can have the best equipment, the best construction, all the safety policies and methods, and still have problems if the employees are not properly trained. In fact, the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration, OSHA, has specific regulations regarding scaffold training. For users, it is expected that these workers will be trained in fall, falling object, access, electrocution and overload hazards. For erectors, training must include additional requirements including proper erection techniques, design criteria, scaffold load-carrying capacity and the intended scaffold use. And finally, for those of you who forget your training, retraining in the hazards is required.

Scaffold Capacity: There is a limit to how much a scaffold can hold. And that limit may be considerably less than what you think. Remember, overload is not the same as failure. Just because your scaffold is still supporting all that brick doesn’t mean it isn’t overloaded—since scaffolds are required to support 4 times the anticipated load, an overload means you are cheating. While the capacity of a frame scaffold varies significantly, depending on the frame style and manufacturer, a reasonable load per leg is 2,000 pounds, which means that if you have any more than one level of brick or block, you may very well be overloading the scaffold. (Lucky for you, most safety personnel and compliance officers have no idea if the scaffold is overloaded, so you may not get cited for infractions.)

Electrocution: Don’t mess with electricity—you normally never get a second chance. Assume all lines are energized and stay at least 10 feet away unless you know how much electricity is in the line. Even then, stay 10 feet away, if not further. Call the power company; they will help you (to deal with the electricity, not lay brick).

Platforms: Each platform has to extend from the face of work to the guardrail system, leaving no more than 1 inch between planks. Most masons use solid sawn scaffold plank, laminated veneer lumber (LVL), of fabricated decks. Traditionally, the plank span no more than 7 feet. For solid sawn scaffold grade plank, the capacity is 500 pounds. Check with your manufacturer/supplier for LVL capacity, although for most LVL, 500 pounds is a reasonable load.

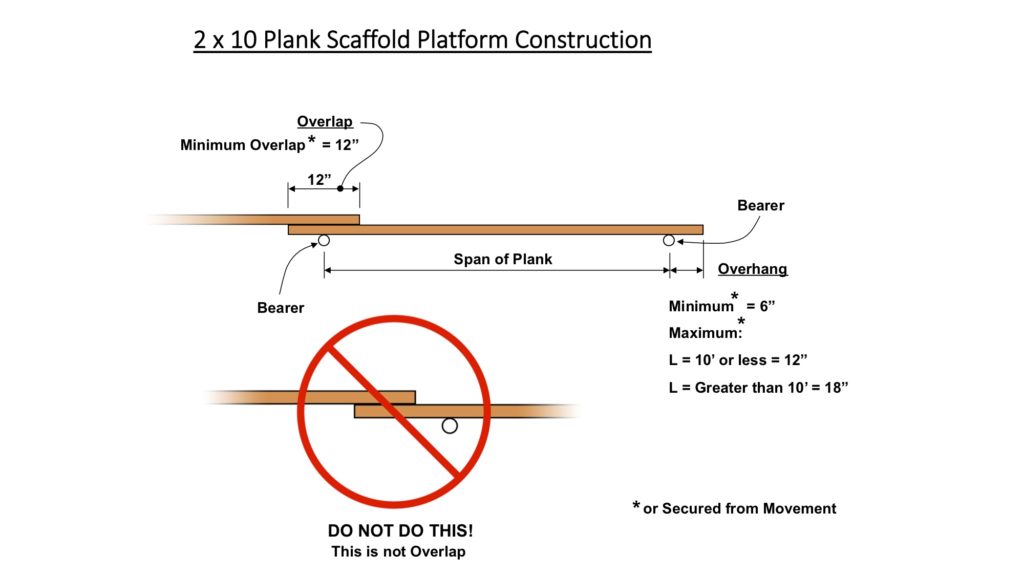

When using fabricated decks, such as aluminum hook decks, limit the load to what is indicated on the deck, usually 50 or 75 pounds per square foot. (Multiplying the width of the deck by the length times the load rating will tell you the total load you can put on the deck. For example, for a 20-inch wide, 7-foot long deck rated at 50 psf, the total capacity is 580 pounds spread out over the deck.) Overhang your plank at least 6 inches but normally not more than 12 inches, Figure 1. On hook plank, check the hooks for cracks or damage. And no, there is no such thing as an OSHA “approved” plank.

Foundations: A scaffold is only as good as its’ foundation. If you are sinking up to your knees in mud, so will your scaffold. Most scaffold erectors evaluate the suitability of the foundation based on experience, which appears to be acceptable to most folks. What is not acceptable is using a perfectly good 2×10 wood plank for a sill and then using it as part of a future platform. Never use a plank in a platform when it has been used as a sill. For most masonry scaffolds, where the leg load is about 2,000 pounds, and the soil capacity is a typical 2,000 pounds per square foot, a wood 2×10, 24 inches long, will suffice. If in doubt, talk to someone who knows dirt!

Scaffold Stability: Scaffolds have been known to fall over and if you happen to be on it when that happens, the experience will not be an enjoyable one. Scaffolds are considered stable if the height is not more than 4 times the width. Therefore, on a typical 5-foot wide scaffold, it must be tied to the wall at 20 feet. After that, the ties can be spaced up to 26 feet with the last tie near the top of the scaffold, no more than 20 feet down (on a 5-foot wide scaffold). Horizontally, tie the scaffold at each end and no more than 30 feet in between. If you plan on enclosing the scaffold, don’t use these tie spacings. Contact an engineer who can calculate the wind loads.

Falling Object Protection: This is easy. Don’t let anyone under the scaffold where they can get beaned on the head or shoulders by a dropped brick. If you must have someone work under you, then use whatever it takes to stop bricks, or the lunch bucket or anything else, from becoming missiles. If you decide to use toeboards, make sure they are at least 3-1/2 inches tall, tight to the platform, and can hold at least 50 pounds.

Access: When the distance from the ground to the platform, or between platforms, exceeds 24 inches, the platforms must have at least one form of access, usually a ladder, a frame you can climb, or a stairway. It is common for masons to climb the frames. This is acceptable as long as the rungs are at least 8 inches long, the rungs are uniformly spaced, and the space between rungs is no more than 16-3/4 inches, Figure 2. Don’t forget that this also applies to the vertical distance between the platform and the work platform on the side brackets (outriggers).

Here is where it can get difficult. Scaffold erectors are allowed to climb frames where the rungs are less than 8 inches long and the distance between rungs in no more than 22 inches, Figure 3. This means that the erectors can climb most open/walk-thru frames. Unfortunately, if you are not an erector, you cannot climb those frames even if you climbed them as an erector in an earlier life, or even earlier in the day!

Fall Protection: This should be a no-brainer, particularly since it is easy for safety personnel/compliance officers to spot violations from the ground or comfort of their vehicle. If they can spot, so should you be able to. Simply stated, fall protection is required once the platform is more than ten feet above the level below. No playing games here—falls are the major cause of injuries or death, and, there is no reason for it. It is easy to install guardrails in most instances, and when it is difficult, or impossible, then personal fall protection systems can be used. What’s more, the scaffold itself can be designed to be used as an anchor for a fall arrest system, even for the scaffold erectors. Figure 4 shows the heights of toprails for various jurisdictions.

If the numbers work, cross-braces can be used as part of the guardrail system. Figure 5 shows how the cross-brace may be used as either the top or mid rail, but never both. In some instance, the cross-brace can be used as neither. And don’t forget, when you remove the rails to load the platform, the exposed employees must be protected against falls, typically by utilizing a fall arrest system, or perhaps a fall restraint system.

Tape Measure: Experience indicates that those who are responsible for the enforcement of applicable regulations, but don’t know the regulations or subject matter, resort to the use of tape measures to ensure regulatory compliance. Think about it: is it not easier to see if the plank overhang is at least 6 inches than calculating the load on the scaffold? Is it not easier to measure the first step at 24 inches than it is to see the bracing is correct? So, if nothing else, make sure the numbers are correct, especially the 36-inch extension on the portable ladder. Everyone seems to be looking for that one, even when no hazard exists.

This is a quick discussion addressing some of the common safety aspects of scaffolding. The OSHA Department of Training & Education developed, based on statistics, the “Five Most Serious Hazards” that work well when evaluating a scaffold. The 5 hazards are: Falls; Unsafe Access; Struck by Falling Objects; Electrocution, and; Scaffold Collapse. Note that the first letter of each hazard spells “fuses,” an easy way to remember the hazards.

David H. Glabe, P.E. has over 46 years of experience in the scaffold industry. He is a member of the ANSI A10.8 Scaffold Committee, a Director for the Scaffold & Access Industry Association (SAIA) and Mr. Glabe provides training and expert witness services for the Construction Industry. He can be reached at dglabe@dhglabe.com.