Words: Ashley Johnson

Photos: Matthew Filstead

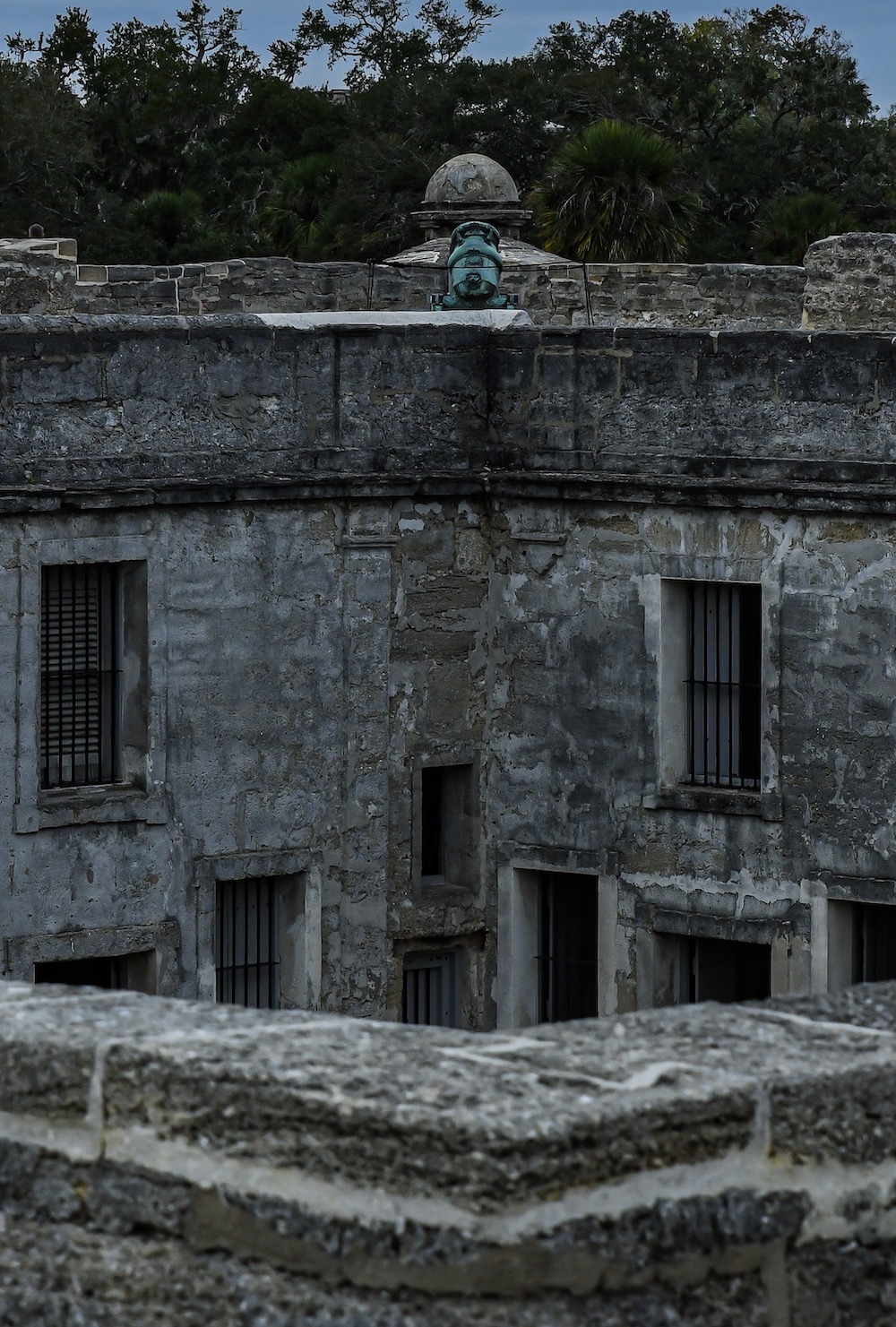

On a typical day in St. Augustine, Florida, the sun shines down constantly from a clear blue sky free of clouds, while the hot humid air shimmers in the distance. Just a five-minute drive south, rising from the banks of the western edge of the Matanzas River, emerges the Castillo de San Marcos. This historical landmark is entrenched in a turbulent and destructive past that traverses back more than 300 years. This treasured monument of Spain’s struggle to maintain control of Florida is recognized not just for its compelling yet chaotic history, but perhaps more importantly how its defenses survived against such aggression and attacks.

The Tactical Beginnings of the Castillo

St. Augustine was founded on September 8, 1565, by Spanish admiral and explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. Strategically located inland from Matanzas Bay, St. Augustine provided convenient access for Spain’s treasure ships to routinely sail back and forth to South America and the Caribbean.

Situated on an inlet of the 23-mile-long Matanzas River, the Castillo was built by Spain in 1672 to protect the town of St. Augustine, Florida. As the oldest masonry fort in the United States, it took the Spanish more than 20 years to complete the Castillo.

By the time it was finished, Spain had a sturdy and impenetrable fortification designed to protect its most valuable trade asset, the town of St. Augustine, which sat on the Atlantic sea route to the Caribbean. As the oldest and continuously occupied European settlement within the borders of the United States, behind French-founded Fort Caroline, St. Augustine was consistently at risk from a multitude of threats.

Before the construction of the current Castillo de San Marcos, nine previous iterations stood in its place, all constructed from wood, all destroyed or burned to the ground. The need for a more enduring structure that could withstand the onslaughts of attackers and protect the southeastern sea route for Spain’s treasure ships came as the result of a couple of notable events.

Imminent Peril From Pirates

Spanish galleons carrying valuable spices, gold and silver, and other profitable commodities faced constant threats from attack by notable pirates. These ships left Havana, Cuba, and sailed up the very narrow gulf stream, which flowed at about three to five miles per hour. Because of the speed at which the gulf stream flowed, as well as how narrow it is at the Bahama channel, it was very attractive for attack by pirates.

The construction of the Castillo was presaged by two notable events directly linked to St. Augustine. The first came in 1586 when pirate Sir Francis Drake came with 42 ships and 2,000 men to burn down St. Augustine. He drove the Spanish settlers into the wilderness, but lacking forces and authority to establish an English colony, he left the town leaving destruction in his wake.

The second attack by renowned pirate Robert Searles came in 1668 with just 100 invaders. Despite St. Augustine having limited defenses, Searles ultimately left the town nearly untouched. This event triggered the need for superior protection in case of a third attack.

Construction of the Castillo

Work began on the Castillo on August 8, 1671, led by Ignacio Dazo, a skilled engineer from Havana, Cuba. Dazo planned the design of the fort in a bastion style, a type of architecture originating from Italy in the 15th century, yet adapted to technology brought about by the change in weaponry.

This bastion style of architecture can be identified by four projecting diamond or angle-shaped formations added to the walls that when seen from above resembles a sea turtle. It is designed to withstand and avoid the impact of cannon fire, while also permitting cannons to be mounted defensively atop the walls.

Laying the foundation of the fort was difficult and complex because of the sandy, unstable soil on which the fort sat. Additionally, with the cooler months, much of the workforce was wiped out by contagion.

To establish the foundation, a trench was dug five feet deep and 17 feet wide. Masons laid two layers of Coquina blocks on the hard-packed sand. About a foot inside this wide foundation, masons stretched their line marking the curtain wall that would taper gradually from 14 feet at its base to about nine feet at the top (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47216/47216-h/47216-h.htm).

Essential Stone

The type of stone used to build the Castillo was also the secret to its survival. The Castillo was built using a coquina shell, a semi-rare limestone that is light and porous. It was the only available material to the Spanish on the northeast coast of Florida at the time and mined from nearby Anastasia Island.

Coquina is a sedimentary stone that is formed from the tiny coquina clam donax variabilis that lived in the shallow waters off the coast of Florida. When the clams died, the remaining shells accumulated in layers upon layers for thousands of years, forming submerged deposits several feet thick. Soil, trees, and other vegetation covered the shells over time. Carbonic acid from carbon dioxide and rainwater percolating through dead vegetation and soil penetrated down through the ground into the shells, leaching calcium from the shells and bonding them together to form a stone.

Most limestones are composed of fossil material or other carbonate grains held closely together by a hardened matrix of crystals of calcite cement that are chemically precipitated between grains. Coquina has no such matrix and only a little cement. This leaves empty spaces between the shells. The result is a light, porous rock with a texture similar to a granola bar.

The advantage of using this light limestone is millions of microscopic air pockets that make the stone compressible. Cannonballs fired at more solid material would cause the material to shatter. Alternatively, cannonballs aimed at coquina constructed walls results in the balls burrowing into the material and getting wedged or stuck. Similar to a BB fired into Styrofoam or a knife into cheese, you get a cannonball hole that is less than 2-feet deep.

Mining Anastasia Island

Coquina was quarried from nearby Anastasia Island, a 14-mile long barrier island that sits east of St. Augustine. Only about 175 workers were actively employed at any time during the construction, which resulted in the amount of time it took to construct the Castillo. Workers and masons originated from Cuba as convicts, as well as Timucua, Guale, and Apalachee Indians.

As the weather cooled and the mosquitoes were not so active, the coquina pits started operating, led by quarry overseer Alonso Díaz. Additionally, two large lime kiln pits were constructed at the site of the Castillo where an old wooden fort previously had stood, about the same size as the Castillo now, but rotted and unfixable.

The workers built large, square-end dugouts and laid rafts over them to haul stone to fortify the area, and firewood and oyster shells for the lime kilns. In the lime kilns, once the oyster shells grew hot, they changed to high quality, quick-setting lime.

Deep grooves were cut into the soft, yellow top layer of coquina. The workers used pry bars and wedges to loosen and extract rough blocks of coquina. These pieces were extremely heavy because of the amount of water still in them, but they were small enough that workers could carry them on their shoulders.

The coquina blocks were then hauled to the wharf by oxen and across the Matanzas River on barges to the work yard, which is now the parking lot for the Castillo.

Because of how porous the stone is, after emerging from the ground they were waterlogged and had to sit outside in the sun for six months to one year until all the moisture had evaporated. Masons could then cut down the slabs and form them into management blocks to build the Castillo walls.

Given that moisture was a persistent and pernicious problem with the coquina building blocks, it was necessary to protect against any future moisture and water incursion. The Spanish plastered both the inside and exterior of the Castillo to waterproof the walls.

Defensive Architectural Design

Several critical tactical and strategic advantages arose from using a bastion style of architecture to erect the Castillo.

Each of the four bastions held dozens of cannons, each accompanied by four soldiers and a general to maintain control and protect all angles of the Castillo. This design also meant that there were no blind spots anywhere on the Castillo walls, preventing any invaders from sneaking closer. By interlocking fields of fire with cannons, any spot around the exterior of the fort could be fired upon from multiple angles.

Upstairs atop the walls of the Castillo, there was access to 70 cannons. At one point, the gun deck held more than 60 cannons made from cast iron and bronze. Each of these cannons was so powerful that they were able to fire projectiles from one mile to three miles.

Additionally, the cannons could fire cannonballs weighing 16 pounds, 18 pounds, and 24 pounds. At the time, the standard load of gunpowder constituted half the weight of the cannonball. If a 24-pound cannonball was being fired then the total load, including 12 pounds of gunpowder, would be 36 pounds. Some of the cannonballs were not standard cannonballs. Instead, these cannonballs included bar shot, chain shot, and the Spanish or spike shot.

Alongside the cannons are hotshot ovens. These ovens created cannonballs onsite and at a moment’s notice to then fire at invading ships that would then be destroyed in flames.

Fighting Features of the Fort

In addition to having a style of architecture that supported the Castillo’s defense, several other features augmented the fort’s strategic and tactical defensive advantages.

Surrounding the Castillo is a moat that could be flooded, raising the sea wall. However, this moat was kept dry and acted as a place to house the Castillo’s livestock. During sieges, more than 600 head of cattle occupied this space, as well as residents’ other food supplies. Not only did the moat house critical supplies for the Castillo, but it prevented invaders from attacking the walls with battering rams.

Another line of defense installed at the Castillo was glacis. This feature appeared as an artificial slope or sloping hill that surrounded the fort and was built to protect the city. The glacis protected the fort’s foundation against incoming fire and artillery. It also prevented the enemy from accessing the foundation while also concealing and covering the soldiers’ movement and maneuverability inside.

The third line of defense protecting the Castillo was of course the type of material used in its construction. The Castillo is one of two fortifications in the world constructed using coquina. The other building is Fort Matanzas National Monument located 14 miles away.

Because of the nature of this stone, cannon fire is absorbed and reflected. This might be key to the fort’s sustainability and why, despite three sieges in Castillo’s history, the walls have never been penetrated by enemies.

Enemy Attacks on the Castillo

During its existence under Spanish rule, the Castillo has undergone three sieges. The first attack came in 1702 by British forces from Charleston, South Carolina. General James Moore and his forces surrounded the fort and occupied the homes of the residents of St. Augustine, who sought safety in the Castillo.

Despite having 800 soldiers, Moore was not equipped to tackle the fort, having only four cannons. While waiting on reinforcements from Jamaica, two Spanish men-of-war blocked the harbor and forced Moore to retreat, but not without burning St. Augustine to the ground. Moore’s siege of the fort lasted 51 days, landing the Spanish their first victory.

After this attack by British forces, a Cubo Line protecting the north of St. Augustine was constructed from palm logs and consisted of a small ditch. Another wall was built along the San Sebastian River, protecting the city’s western area.

In 1740, the British attacked the Castillo again, but this time from Georgia by British Governor James Oglethorpe. The siege lasted 28 days with Spain once again victorious.

The third siege on the fort came in 1812 from the United States, who attacked from Georgia during what is known as the Patriot War. This assault lasted six months, ending in Spanish victory yet again. After this third attack, the Spanish erected earthwork lines around St. Augustine to protect it and turn it into a walled city.

Changes in Ownership

Despite never having been taken by military force, the Castillo changed hands several times through treaty and negotiation by the British, United States, and confederate states of America during the Civil War.

The first foreign occupying force was Britain, which maintained control for over 20 years. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 came about as a result of the United States and Britain defeating France and Spain in the Seven Years’ War, also the French and Indian War. Part of this victory gave control of several French-held Caribbean countries to the British, including Havana, Cuba, one of Spain’s foremost seaports and administrative centers. In the treaty, Havana was traded back to Spain in exchange for Florida to the British. As a result, control of the Castillo was also handed over to the British.

The Castillo was renamed Fort St. Mark and used as a supply base and a prison for captives. One such captured rebel included three signers of the Declaration of Independence: Thomas Heyward Jr., Arthur Middleton, and Edward Rutledge.

The United States took control of the fort in 1821 when it purchased Florida, renaming it Fort Marion for American soldier Francis Marion who served as a military officer in the Revolutionary War. The United States used Fort Marion as a military prison during the Revolutionary War to house detainees. Native Americans also were imprisoned at the Fort during the First and Second Seminole Wars. One notable detainee housed at the fort was Seminole warrior Osceola.

Osceola tenaciously resisted the United States’ forced removal of American Indians and urged Florida Seminole Indians to fight for their lands. He was captured after a treaty meeting with American officials and under a flag of truce just west of St. Augustine during the Second Seminole War. He ultimately died from a severe throat illness that stemmed from tonsillitis in 1838.

In addition to Osceola, about 200 other Seminole Indians were imprisoned at the fort. One of the most acclaimed events during this time was the escape of 20 Seminole Indians from a small room about 20 feet square. The only light came from a small hole 18 feet above the floor (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015056463840&view=1up&seq=44), from which they escaped, and is said to be only 8 inches wide.

The Fort’s Later Years and Today

The Castillo was decommissioned in 1900 and 1924 was designated as a national monument. Ultimately it reverted to its original name of the Castillo de San Marcos.

Today, a major concern is how to preserve the Castillo’s exterior so it lasts another 300 years. Recently, large cracks have been observed in the walls of the fort. According to James Crutchfield, project manager at the Castillo, these cracks first became apparent when there was water in the moat. The moat was flooded with water from 1938 to 1996. Once these cracks first became visible, the moat was emptied so the cracks could be repaired.

Nevertheless, the damage is still being caused to coquina stone blocks as proven by discoloration. When water drains from the Castillo’s gun decks through drainage spouts, it drains directly onto the walls. This allows plants to grow in the stone bricks and damage the coquina.

Starting in 2020, the goal and plan are to repair areas where plants grow by creating a lime mortar sacrificial layer and then spread it over the sides of the walls. This will protect the coquina bricks from further erosion and prevent plants from growing onto the lime mortar.

The Castillo de San Marcos represents a legacy of endurance, purpose, and brilliance in engineering, both military engineering, and architectural engineering. Control and ownership of the fort changed hands six times during its history, always through treaty and negotiation, never by combat.

This structure is a testimony to history and how adaptation, use of natural resources, and utilitarianism can lead to enduring and beloved monuments that remind us of our capabilities and abilities in architecture.