Words: Jayson Kellos

Photos: Hohmann & Barnard, CBCK-Christine

The first step in recognizing, tackling, and preventing efflorescence is educating yourself on how to recognize the issue. Using best practices and procedures throughout the build will aid in prevention. Just as important is using quality materials for not only cleaning but also preventing, efflorescence.

As a mason contractor, it’s important that you keep communication with designers and other trades open regarding possible problem areas. This always should be a goal since, let’s face it, the design also can be at the root of the problem. No matter how the masonry is installed, treated, or maintained, the design and foundation of any project must be correct.

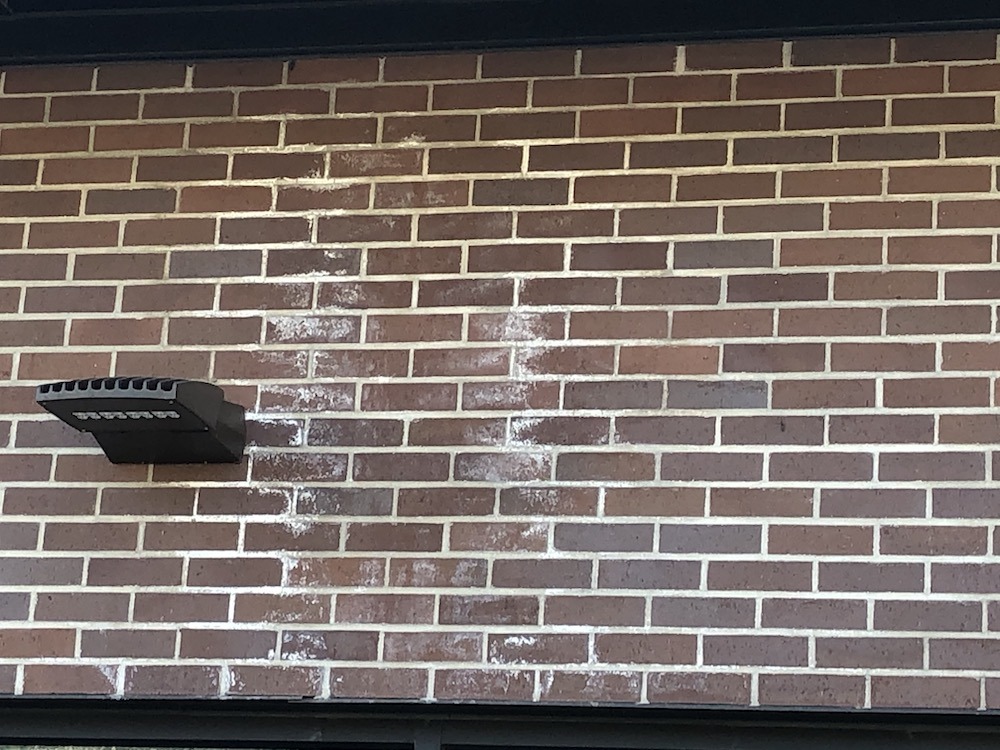

Let’s look at the early warning signs of efflorescence, its root cause, and any damage that may result. The earliest sign of efflorescence is caused by a constant or repeated water source infiltrating cementitious materials without the ability to breathe and dry out. In the beginning, it may simply look wet all or most of the time.

But during this time, the masonry is constantly storing more and more salts. Eventually, these salts will migrate to the surface and dry. If the masonry is storing moisture or water, efflorescence will likely occur at some point. The constant or repeated water source is a warning sign of future efflorescence.

Diagnosing and Treating

Efflorescence will look clear – or nearly clear – while it is wet. You may see only a mild haziness. Keep in mind, if you’re seeing a bold, white substance when the problem area is wet, you are looking at a different problem. This could be hard water, hard calcium, lime run, or even white paint.

If you put salt in a glass of water, it goes from a white to a hazy, almost clear substance. Since efflorescence is basically salt buildup, it’s no different. It will often wipe off on your finger as a powdery substance, and taste like salt, should you use this method to identify it.

Once you’ve identified efflorescence on your masonry wall, the first step in treatment is finding and confirming the problem or source of water intrusion and repairing it. Once the problem or source is fixed, efflorescence often will go away on its own.

New masonry will commonly have some degree of efflorescence, because of the water used in the installation process and its contact with cementitious materials. This is called “new masonry bloom.” Understanding the difference between new masonry bloom and an actual reoccurring presence of water is important. New bloom will likely disappear on its own, throughout the initial curing process or during the initial washdown.

Once you’ve identified the source of the problem, address it immediately. Cleaning or removing the efflorescence is not enough; it will return in a short time. When treating the efflorescence, never use harsh acids. Specific, specialized cleaners are always the best. Assure the cleaner is intended for the material being cleaned, to ensure no unwanted damage, etching, or color changes occur.

Avoid using high pressure when washing off efflorescence, since driving moisture deep into the surface will only add to the bloom. Water is the source that feeds efflorescence, so use as little volume and pressure as possible when during removal. Effective cleaners that do not require the use of water are available on the market for this specific reason.

Strong cleaners and harsh acids are often used, and although these types of liquids might clean the efflorescence off of the surface, rinsing them off requires a lot of water. This supports more bloom. They also can damage materials and will actually promote more efflorescence.

Maintaining and Protecting

Masonry is extremely resilient. By design, it can withstand getting wet and drying out without issues. Maintenance issues often occur with other materials in contact or relationship with the masonry. Think sealant and caulk joints, roof flashing, wall caps, parapet caps, and leaky downspouts. Sprinklers that are improperly aimed or adjusted, and are soaking the masonry daily, present another issue. All of these areas will continually allow water to intrude in locations other than the face of the surface.

Ultimately, keeping the masonry free of voids and open cracks, and therefore maintaining its continuous surface, is the best method of maintenance. This includes sills with full, struck head joints, preferably with through-wall flashings installed beneath them. In cavity walls, keep the weeps free and clear of debris to promote proper cavity ventilation.

Protecting the masonry during construction can help prevent the problem of efflorescence. Keep your materials off the ground and covered. As simple as it sounds, it is effective. Keep walls covered when you’re not working on them. Always use clean, potable water when mixing mortar, cement, grout, etc. to help eliminate other alkali or impurities. Keep cavities as clear as possible to eliminate mortar bridging.

It comes down to using best practices throughout the build, right down to properly installed weeps, and adequately full head and bed joints. The fuller they are, the less room there is for water to accumulate. Regarding weeps, they are only as good as the mortar collection devices being used. Keeping the sluffed mortar from blocking the backside of the weep is a must.

Efflorescence Vs. Bloom

Keep in mind that brickwork with efflorescence bloom can be deceiving. Efflorescence often covers the face of the brick units as well as the mortar joints. The source is usually water reacting with the mortar and not the brick, but migrating across the surface of the brick.

Efflorescence also can be mistaken for other stains that are simply that, rather than a blooming reaction. Hard water, rust, and other minerals are deposited to the surface, staining it. These are stains, not blooms. Lime run is sometimes mistaken for efflorescence and should be addressed differently than efflorescence bloom. Differentiating the two will allow you to dispel misconceptions and treat each problem accordingly.

Jayson Kellos is Architectural Representative – Western Region, H&B by Powered by MiTek.