Construction aggregates form the underpinnings of our cities, towns and transportation networks.

Thousands of years ago, civilizations built entire cities with stone, sand and gravel,

and many of these ancient structures exist today.

[vulcanmaterials.com]

From the perspective of any quarry owner, crushing rock is what it’s all about. To the guy or gal operating something like the Cat 349F L hydraulic excavator, hey, crushing rocks, like it’s kind of fun to move a handle that transmits so much power to a set of jaws that can reduce a big boulder to little rubble in a matter of seconds ~ fun coupled with serious responsibility and acute operator skills. In the first example, crushing is the verb, and in the second one, rocks is the verb.

Fabrication of rock goes through three well-defined stages:

- Blasting to loosen the rock

- Loading up to move to refining stations

- Sorting, crushing, sifting to shape and reduce the rock to aggregate, sand and gravel

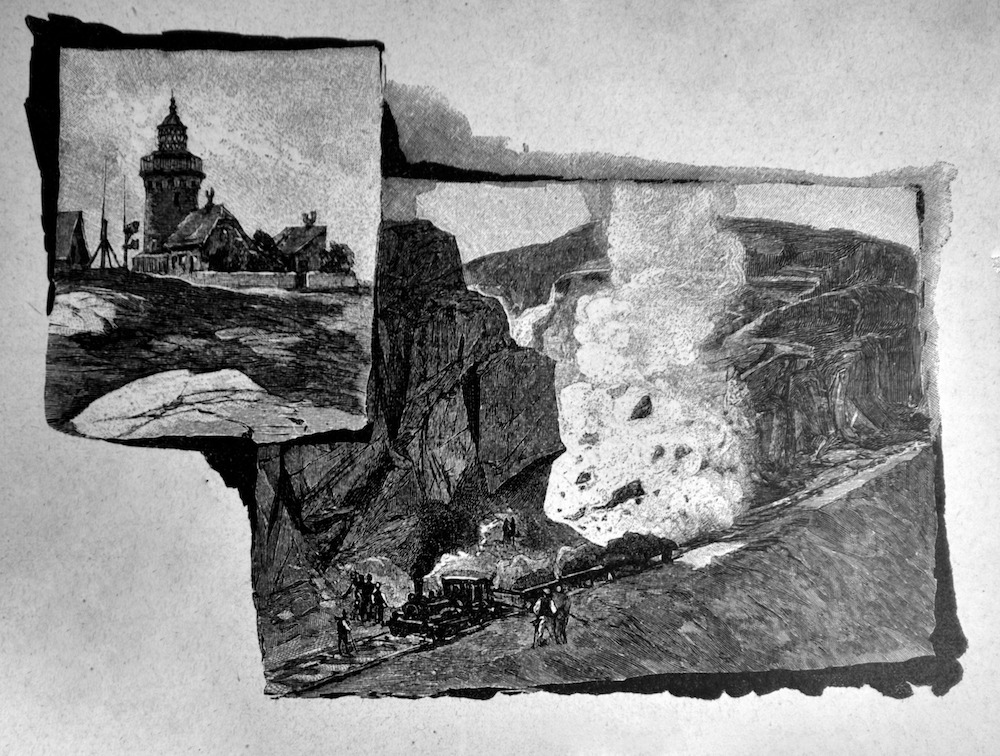

Blasting Rock

As more than 80% of rock is reduced to small rock aggregate, gravel or sand, explosives are the preferred method, though not the only one, of loosening Mother Nature’s grip on her rock beds. Some quarries blast as much as three days a week, and others may need to do it only two or three times a month. Each blast needs to be professionally managed in terms of safety and efficiency. Large quarry companies may employ specially trained and licensed people to order, store and handle the explosives. They are readily available on short notice to service any of a company’s quarry sites. Small quarries, however, may subcontract blasting activities.

Dykon Blasting, based in Tulsa, Okla., has a quarry division which offers drilling and/or blasting programs for the aggregate industry. “Each quarry has unique needs which are specific to its operation. We provide each quarry with a specialized analysis identifying its specific needs and then develop a tailor-made blasting program to fit those requirements. Every decision we make is predicated on the safety of the public, our partners and our employees.” [www.dykonblasting.com]

Dykon’s Quarry Blast Programs address:

- Safety

- Neighbor relations

- Geological analysis

- Production rates

- Plant capacity

- Final product requirements

- Profitability

- Fast and reliable service

Once blasting material has been strategically placed into vertical holes that may run as deep as 50 feet, with rock inserted above the explosives, and be located up to 20 feet apart, the ensuing explosion forces rock to move 100 to 200 feet forward. It’s more like an implosion than what one might envision for an explosion. “Benches appear depending on how deep the holes were drilled,” explains consulting geologist Alan Gensamer. “Bench dimensions can be designed to fit the extraction process, truck size, loading method, rock stability, etc. If rock integrity is a concern, holes are also drilled, but the explosives are controlled in size so that the rock is cracked and not shattered.”

“In the granite quarries of the Northeast, they drill vertical holes and split the rock using metal wedges and ‘feathers’ pounded in with sledgehammers,” Gensamer continues. “Slate and softer rocks can be cut by cable saws that are like huge band saws. Giant diamond saws are even used in some places.” However, there are not very many effective alternatives to blasting for quarry businesses which move, crush, sift and handle thousands of tons of rock every day.

Loading Rock

The blast leaves a large pile of loose rock, and some mighty heavy equipment rolls in. Quarries are not very crowded places, and most days host a small variety of very heavy, very slow-moving equipment with all kinds of buckets, front loaders, crushers, swivel and dumping capabilities. Since rock is very heavy, it is not economically practical to move it any farther than necessary, so many of the crusher stations and conveyor belts are strategically situated near the blasted pile for loading, dumping, sorting and moving material toward its destination.

The most common heavy equipment includes:

- excavators

- front end loaders

- haul trucks

Excavators come in three size categories, appropriately small, medium and large, like tee shirts. The largest ones offer 380 to 500+ horsepower and weigh between 100,000 and 200,000 pounds. The large price tag starts around $400,000 to more than twice that depending on features and upgrades. The large front end or wheel loaders carry recommended sticker prices of $800,000 to more than $1 million. Just one set of new tires can cost $100,000.

Curtis Dorwart, vocational marketing manager for Mack Trucks, praises the advances in 3-axle dump trucks. Engines can go a million miles and not need an overhaul every 100,000 miles. “These days with EPA emissions regulations and high-tech engines, the expectation is for longevity, so we have to put out as robust a product as possible to meet a 7 to 10-year retention cycle,” he says. “These days you’re going to get a lot out of the motor, transmission and rear end. Usually what it comes down to are things like suspension components wearing out, rubber bushings, worn kingpins, torque rods, cracked cross-members or brackets.”

“Aside from driver wages, fuel and tires are the biggest operating expenses on a dump truck. Class 8 models typically get around 3.2 gallons per hour for short hauls, and 6.2 mpg for highway hauling. Dorwart notes that gallons per hour might be a better metric to use off-road especially if a truck is doing short hauls, building stockpiles, moving rock from the excavator to the crusher and such.” [www.equipmentworld.com]

Front end loaders may be the most efficient equipment on terms of moving rock, and each dump truck, excavator and front end loader runs about $150 to $300 per hour to operate. It’s not rocket science to do some quick math that adds up to thousands of dollars pouring out of the coffers like rocks pouring out of the loader bucket in just one work shift. On the safety and convenience side, the drivers and operators are much more comfortable than a couple decades ago with air conditioning, ergonomic controls and seats and noise suppression. No doubt there are cup holders and a radio to boot.

The front end loader scoops the blasted rock and not very graciously but accurately dumps it into the bed of a haul truck, which moves to a primary crusher. Crushing rocks can occur on the quarry surface near the pile or down in the pit, which has two advantages: It costs less to get the load there for moving down hill, and it shields neighbors from noise. At a new site, of course, the crushing occurs on the surface.”

Crushing Rock

Rock crushing has been automated over the past few decades with software engineering, computer controls, cameras, drones and robotics integrated into the process. Erik Westman, PE, Ph.D., Professor and Department Head at Virginia Tech’s Department of Mining and Minerals Engineering, says automation and the use of drones have dramatically improved human safety and efficiency. “Ten years ago there would be employees standing and watching the crushing operations at several points for problems with the load or equipment. If a section got too full, one of them would hit a switch to halt everything and remedy the issue. The work is dirty, dull and dangerous. Now most of the crushing operations are monitored by cameras which constantly relay information to a computer which can then stop or slow down a section in the process.”

There are many steps to take bowling ball size rocks or bigger to pea gravel pieces or smaller. The most common primary crusher is the jaw crusher. An assortment of chutes, conveyors and feeders carry rocks to secondary and tertiary crushers and screens. Crushers reduce the size of rocks, and the screens sort them. In some operations, there are several screens above one another as large as 10 by 20 feet so several products are being sifted and dumped into surge piles at the same time. Some automatic systems are set up for the rock to get crushed again and circle back through the screens. Others have the screens periodically dump their load sideways.

Westman’s Virginia Tech department is renowned for cutting edge research and hosts mining experts from around the world. “Over the past 10 years, more than 20% of all U.S. mining engineers have graduated from Virginia Tech, and about 40% of our grads go to work at aggregate quarries. We are heavily engaged with the industry,” he says, “and it’s exciting to see drones come into play. To figure out how many tons of a specific product that a quarry may have on hand, a couple people might stand back near a surge pile and make an educated guess on its size, tonnage and value. Now, a drone takes pictures that feed into software which does the calculations for dimensions then weight. Another great advantage of drones is surveying active quarry equipment. You can have a conveyor belt 100 feet high with no safe way to get up there to inspect it routinely. With drones feeding photos from different angles, one can see where a pulley is starting to fail or a conveyor belt is fraying.” Drones can take the element of surprise out of equipment failure, which increases efficiency and dramatically reduces downtime.

With all this rock crushing going on continuously, there is a major dust situation to address for employees, equipment, neighbors and communities. The two main approaches are:

- suppression

- containment and collection

Water is the best way to suppress dust with sprayers continuously emitting a mist or spray over much of the crushing process. Programmed dust suppression systems offer yet another place for automation to shine. Most of the stationary, computer-controlled water systems run through pipes and hoses with adjustable nozzles. Water trucks can go anywhere to keep dust at a minimum, including the roadways within the pit and unpaved access roads. Dry dust collector systems with vacuum capabilities are effective, but much more costly for having to enclose a large portion of the crushing and sifting process. Chemical suppression is generally cost prohibitive as well in terms of cost and administration, as it must be accurate to be effective.

Most quarries are open normal business hours, with some running two shifts and others with operating permits which do not allow opening earlier than 7 a.m. or perhaps later than a certain time, considering close neighbors or communities. There are many quarries across the country because of the exorbitant cost of transporting such heavy loads. Most quarry operations serve a limited region, and often the cost of hauling exceeds the price of the load. But it is precisely the quarry operations that keep the whole country in roads, bridges, driveways, house foundations, bricks, pavers and millions of conveniences and necessities.

Joanne M. Anderson is a southwest Virginia freelance writer and DIY small farm owner. She feels exceptionally small at the ocean and when picking up a load of pea gravel at the local quarry to reduce mud under her pasture gates.

Sidebar 1:

Braen Stone is a 114-year-old, fifth generation family business based in Haledon, N.J. Its early beginnings are tied to Samuel Braen taking over a quarry as payment for a gambling debt in the late 1880s. Though he knew little of the business, his on-the-job training and entrepreneurial spirit sparked both a profit and the drive to expand. Like many quarries, quality customer service and exceptional career opportunities place the enterprise in the people business.

The following list gives a rundown of crushed stone grades and their best uses. While there may be slight variances in the naming convention of crushed stone, these are the most common names and sizes:

- Crushed stone #5 – Sizes are from 1″ down to fine particles. For road and paver base.

- Crushed stone #67 – Sizes from 3/4″ down to fine particles. For fill, road and slab base.

- Crushed stone #1 – Sizes are from 2″ to 4″. The largest of the crushed stone grades. For larger jobs such a culvert ballast.

- Crushed stone #8 – Sizes from 3/8″ to 1/2″. For concrete and asphalt mix.

- Crushed stone #3 -Sizes from 1/2″ to 2″. For drainage and railroad projects.

- Crushed stone #10 (also called stone dust) – Screenings or dust. For fabrication of concrete blocks and pavers and for riding arenas.

- Crushed stone #57 – Sizes of about 3/4″. For concrete and asphalt mix, driveways, landscaping and French drains.

- Crushed stone #411 – A mixture of stone dust and #57 stone. For driveways, roads and as a base for retaining walls. It can also be used to patch holes in paved areas. The dust mixes with the larger stone and settles well. [list from braenstone.com]

Sidebar 2:

Regarding today’s heavy equipment cab comforts:

Wow! Who wouldn’t want to have their office in a 500+ HP loader with AC, music and a cup of coffee? Every boy’s dream. ~ Alan Gensamer, consulting geologist