In the beginning, an oven was just a hole in the ground — and bricks were just mud-pies. But the oven story really begins with fire. The fire that turns clay into brick is also the start of the human story. No other animal makes fire; and by learning to cook their food, our ancestors were able to develop richer sources of calories and nutrition and make them easier to digest. That nutritional bonus and savings in time then helped us grow brains that could learn to make pottery, fire bricks, smelt ore, forge metal, and make tools, tribes, and societies. That story is also partly why wood-fired ovens are so popular. Despite push-button technology and convenience-oriented marketing, a lot of people are as hungry for the ritual labors of live fire cooking as they are for the good food and party atmosphere.

The particular history of ovens begins long before we started writing, and is all there in the process. First there’s spit-roasting over flame or coals. Then, for big starchy roots and other slower-cooking foods, there’s burying in hot ashes. If the ashes cool off too fast, there’s piling hot stones on top, and covering it all with more ash. Many such practices continue today, as well as showing up in the archeological record, but masonry ovens like the ones we know today only appear with the start of grain agriculture — in other words, bread (and beer — which is the likely source of the yeast used to make the first bread rise).

Ancient Egyptians left drawings of bakers putting dough on a hot rock and covering it with a hot clay pot — the first “true” oven, if you will. From there, it wasn’t far to a clay pot big enough to put a large fire into to heat it hot enough to bake all your loaves at once. Bingo. A bakery to feed all those guys laying the big blocks for the pyramids…

A few thousand years later, tomatoes made their way to Italy so we could have pizza — probably the most popular wood-fired food — but pizza isn’t the only reason to like wood-fired ovens; there is also how the food cooks and tastes. Fifteen years ago, I had just finished building an oven for a new restaurant. The chef brought out a test eggplant in a baking tray, slipped it in the newly hot oven, and went back to his kitchen. A few minutes later, he came out to turn it, but it was already done: “faster than a frickin’ microwave!” he said. And much better tasting.

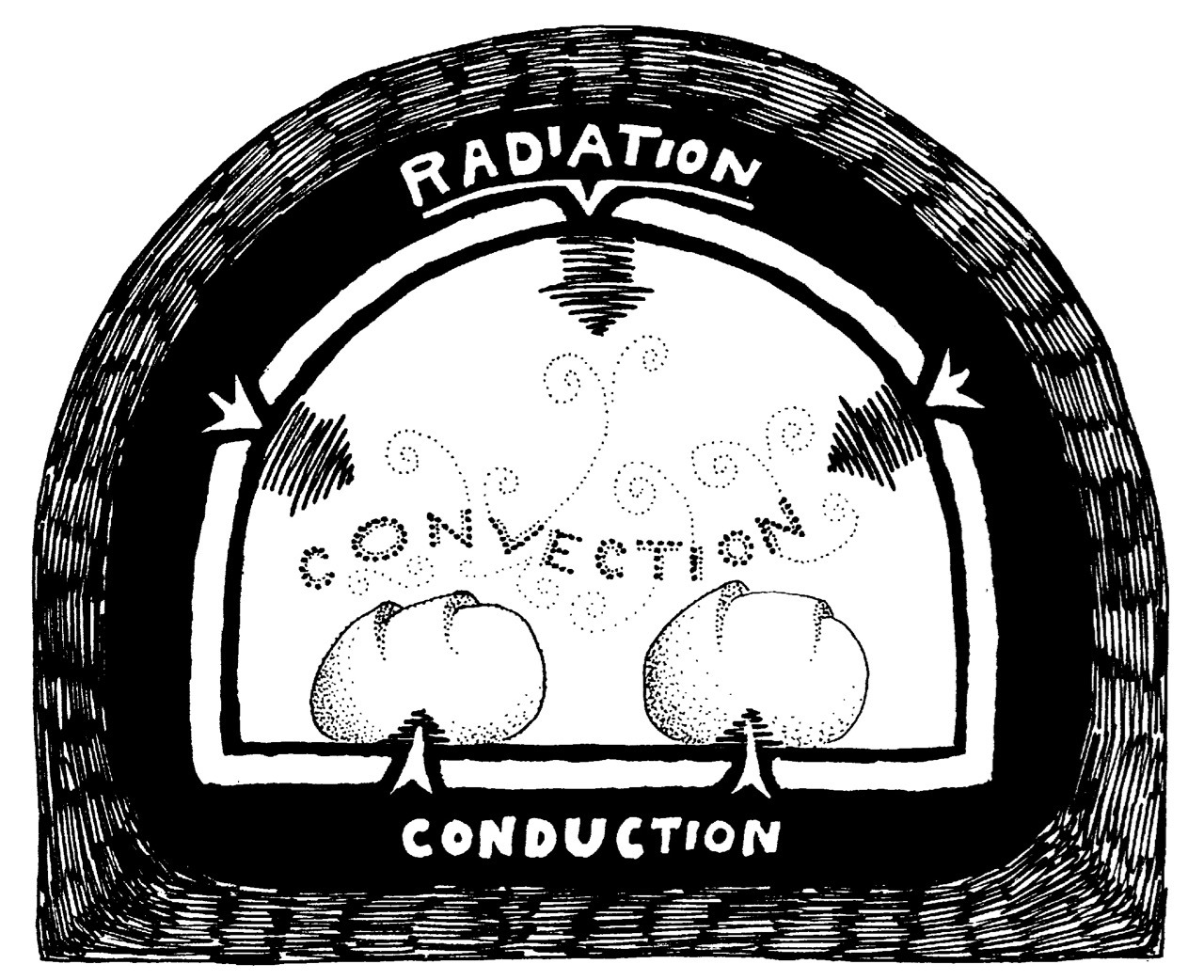

The improvement in flavor is worth explaining: where modern gas or electric ovens cook food by moving hot air around inside an insulated, lightweight box, a wood-fired oven works by soaking up heat, like a battery building up a full charge; then the hot, heavy oven walls release the heat slowly, for hours. Food in a masonry oven is cooked not only by hot air, but also radiant heat from hot dense masonry, and (especially for bread and pizza, which aren’t cooked in pans) heat conducted directly into the food from hot floor bricks (bakers call the resulting added rising action of bread “oven spring.”) Finally, a masonry oven seals in the steam released by cooking food.

That super-charged steamy atmosphere produces a more flavorful and chewy crust, and keeps other foods moist and tender. The triple combination of radiant, conductive, and convected heat also speeds cooking. [see diagram, from Build Your Own Earth Oven, p. 9.]

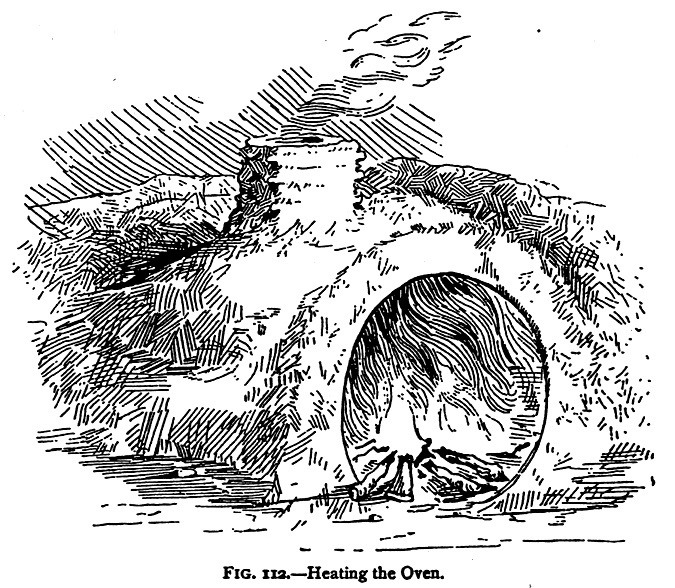

Wood-fired oven-cooking techniques haven’t changed much over the past couple of millennia, nor have construction practices. Whether built with mud, brick, or modern refractories, any oven is basically a masonry shell, a smaller version of such famous masonry as the Roman Pantheon, Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence, or Houston’s Astrodome. Early ovens were simply clay soil (usually tempered, as in brick-making, with sand) laid over a form of sticks or sand. When the clay was stiff enough to cut open a doorway, you dug out the sand, or burned out the wood. Simple. Early brick ovens were also built over formwork, though many cultures developed dome-building methods that required no forms, such as traditional Italian dome ovens.

These are laid up free-form, often only by eye. The first course is a circle of brick or half-bricks; the next course is laid on a wedge-shaped mortar bed. Each succeeding circle of brick sits at a steeper pitch and draws the dome closer to the center. Suction holds the bricks in place until the courses approach vertical, at which point the mason may use a stick as additional support — but only until s/he closes the top of the dome with the central keystone. Perhaps Brunelleschi’s famous formless dome design was partially inspired by an oven?

All these methods are still in use, whether the materials are mud and brick, the latest hi-temp castables, or pre-fab modular ovens. (Modular ovens typically require a mason to install the insulation and finish the exterior — which may be brick, wood, or metal.) In all cases, the ovens typically go under a roof or some kind of weather protection, so the finished structure often looks like a little house.

Square or rectangular ovens can be built w/standard bricks and little cutting. Tapered arch bricks make for easier and stronger vaults — but without buttressing or a steel harness, the weight of the vault will push out the walls and cause collapse. Round ovens, on the other hand, may require a lot more cutting, but generally need less buttressing.

For brick, most masons use standard, 4-1/2 x 9 x 2-1/4 firebrick (though it is still possible to find old, or old-style porous redbrick that can withstand thermal shock and extreme cycling). A baker with a lot of wood-fired oven experience may ask for a particular grade or make of floor brick — and not necessarily the “best” or “highest” — because baking is not just about taking the heat, it’s about how a particular type of brick transfers the heat to the dough.

Density and chemical composition determine the brick-to-bread rate of transfer, which in turn determines baking time and crust development — if the heat moves too fast, the crust burns. If it moves too slow, the crust dries out and gets too thick. People can be particular about their bread! But without getting too technical, if a brick will work for a fireplace, it should work for an oven.

Then there’s mortar. While some builders used lime mortar for ovens, most traditional refractory mortar is just fireclay and mason’s sand. (Portland-based mixes won’t hold up to typical oven temps.) Tight joints increase strength and durability, and commercially prepared refractory mortars offer more aggressive bonding.

Insulation is perhaps the most significant change in masonry oven construction. If you remember your class in thermodynamics, heat is energy moving from higher levels (or temperature) to low. At the atomic level, heat is the motion of all those little atoms and electrons that make up a material. The more the particles move, the higher the heat. Excited particles bouncing off each other transfer the heat, moving it from hot to cold.

Imagine, for example, a gang of little boys with big pockets full of superballs. Bouncing balls resemble excited (hot) molecules. As the boys empty their pockets, the bouncing balls bump into each other and spread out. They bounce farther away, the boys chase after them, the excitement spreads farther. Eventually, all the superballs disappear in the bushes, boys tire out, and bouncing stops cold.

Here on earth, the sun delivers lots of bounce, and the surrounding atmosphere acts like a wall to bounce the energy back in. In outer space, however, there’s nothing — a vacuum — and the bounce all disappears quickly. Not much moves out there. Little motion means little heat, and almost no transfer — very cold. Closer to home, if you wrap your hot coffee in a thermos — a hollow cylinder with all the air sucked out of it — there’s not much to move the energy from your hot coffee to the cold air around it. Your coffee stays hot. (One of my first bosses, an old Norwegian carpenter, fondly said of his thermos: “that coffee burns my mouth in the morning, burns it again after lunch, and still burns it on my afternoon break!”)

Ovens that are actual holes in the ground lose a lot of heat quickly as the ground they’re sitting on sucks the heat out. You can’t wrap a ton of oven brick in a vacuum bottle, but you can slow heat loss by raising it up off the damp ground. The next improvement involved building ovens on wood (as with traditional Canadian clay ovens, where the thickness of the masonry (mostly) prevented the wood from getting too hot…), or on lighter weight masonry, like tufa, pumice. More recently, Alan Scott, called by some the grandfather of modern wood-fired ovens, popularized a practice of building the oven on a lightweight concrete slab made of pumice, perlite, or vermiculite.

Alan further reduced heat loss by extending the rebar through the formwork onto the tops of the side walls, effectively “hanging” the slab (and oven) on the supporting walls. Removing the form left about an inch of air gap to isolate the entire oven structure from the base. That isolation effectively broke the thermal “bridge” that otherwise allowed heat from the oven to leak into the base. Most well insulated ovens use various methods to achieve similar results. Basically, you just need to make sure your baby is well wrapped up before you put it in the stroller…

Commercially available, high-strength insulative board makes a very good, firm, warm “oven mattress” that conveniently solves the problem of weight bearing insulation and provide an easy way to keep the baby off the cold ground. Insulative, lightweight firebrick are another option (these are made of clay mixed with ground up organic matter (wood, nut shells, etc.); when the organic stuff burns out, it leaves thousands of tiny voids in the clay, making a spongey, insulative, and firm foam-like material).

To keep the baby warm on top, there are lots of options for quiltish materials. You can build walls around the oven, crib-like, to make space for a loose cover of perlite, pumice, or vermiculite. For a smaller profile and a rounder look, you can wrap the oven in mineral wool blankets (similar to fiberglass but made from clay or rock and much more resistant to high temperatures and thermal cycling). Mineral wool blankets do need to be covered — either with a reinforced stucco shell, tile, or equivalent. All these options allow many choices for decorative work or ornament.

Since you can calculate the heat storage capacity of a given amount of brick, you can also design an oven that holds just enough heat for what a client wants to cook. Commercial bread ovens, for example, that need to be able to bake hundreds of pounds of dough a day, typically need a lot of extra mass to maintain baking temps. If they’re adequately insulated, however, they never cool down completely, thus keeping fuel requirements lower.

On the other hand, 1-3 hours of fire in a small back-yard bake oven with 2-4” of well-insulated masonry can provide slowly declining baking temps for 12 to 24 hours — more than most people will be able to use. If you just want a pizza oven, however, you really need mass only where the heat contacts the cold dough — in the floor. Since a live flame cooks the top of the pizza, the dome can even be made of thin sheet metal (tho it should still be insulated).

No matter what you build, remember: it’s just a hole in the ground. The mason, on the other hand, serves as more than just oven-builder. Keeper of the hearth-fire, guardian of the hidden dragon, defender of the heart of the home — however you think of your role, every oven you build will feed a lot of mouths beyond your own. The best training is to build yourself an oven and learn to use it. It will teach you things you can’t learn any other way: how to make good pizza, good bread, good food. Where your firewood comes from, and which wood is best for starting the fire, which for heating the oven, and which for cooking pizza.

You’ll learn to split, stack, dry, and store the wood; and the similarities between the trees we grow for fuel and the grain we grow for bread. It also helps to learn to build a fire so it barely smokes at all (burn from the top down instead of bottom up). And for a truly hand-made fire, you can even learn to start the fire by rubbing two sticks together. Through it all, you’ll acquire a deeper understanding of the magic of combustion, and the pleasure of gathering friends and family around fire and food — all that makes us happy, healthy, and human.

FOR MORE INFO: If you’re interested in ovens as a specialty, the Masonry Heater Association of North America offers extensive training and individual support as well video resources and photo-documentation on their website. A non-profit trade association of professional Masons, the MHA focuses on wood-fired masonry heaters and bake-ovens. You can contact Executive Director Richard Smith or visit their website at www.mha-net.org