Once upon a time, stone castles were conceived with protection from enemies as a primary objective. Thus, top of hill locations, moats encircling them, stone construction and access points were all seriously considered. The main entry was usually one level above the ground, and occupants would lower and raise a ladder as needed for entering or leaving the property. Interior masonry stairs were often in the walls or towers and might be straight or spiral. The newel staircase was common, but so also were stone spiral ones which were designed clockwise going up. A would-be attacker would have to expose more of the body turning right to use swords in their right hands. Apparently back then, as now, around 90 percent of people were right-handed.

Thousands of old stone towers are still standing in the countrysides of Ireland and other countries, many with spiral staircases inside. Castle Hartenfels in Torgau, Germany, was built in the 15th and 16th centuries and referred to as an early Renaissance jewel. Restoration began in 1999 of its “Grosse Wendelstein” or “Impossible Staircase”. It is a beautiful, enclosed spiral of stone steps without a central supporting post. Three years later, the final phase of restoration was complete.

It’s possible that this very staircase was the one in David Conroy’s childhood book on castles that he remembered seeing when a buddy asked him to build a soaring, 3-story stone chimney with two massive fireplaces and spiral stone staircases behind them. “I couldn’t find the book or the pictures, but they were in my head already,” states the 52-year-old stone mason. “Jimmy [the homeowner] thinks big, and when he sketched out what he wanted on a scrap of paper, I knew I could do it. Of course, we’d need some sort of official drawing and approval before we could get started.” And thus began the most thrilling project [so far] in Conroy’s 30-year career.

“Sure, I Can Do It”

Conroy had been dreaming about a career in stone masonry since he was about 12. “My parents had to make a rule when we went camping that I could not bring home a rock bigger than my fist,” he recalls, being driven to examine and collect rocks from a young age. In his adult years, when he no longer accompanied the family on camping trips, his mother would always find a rock to bring back to him. No bigger than her fist, of course.

Conroy’s dad was a truck driver, so he learned mechanical skills young and after high school went to work building “high line” power lines until a stone mason named Steve Cohan called. He asked Conroy if he could drive a truck and maneuver it deftly when loaded with rock. “Sure, I can do it,” Conroy said, already familiar with the split gears of a two-speed axle where if you don’t get the rear end back in gear quickly, an entirely loaded truck will roll backwards, sometimes down a hill. Not good for the truck, the rock load, the job, the boss or the driver. After a couple months, Cohan asked if Conroy could lay stone. “Sure, I can do it,” he replied. He worked on brick shelves on the back of a big stone fireplace and found his passion with the first brick. “That launched my masonry career. Steve saw I had the eye and the gift for it, and I was pretty much running the show when Cohan decided to move to the Pacific Northwest five years later.”

In 1997, Conroy named his company Stone Age Masonry and employed up to a dozen on as many jobs at the same time until the Great Recession of 2009. He hung in there, and now he intentionally keeps the business on the small side with a couple employees, taking jobs that challenge and thrill him.

Some 20 years ago, Conroy built a fireplace for Jim (Jimmy) Tannahill’s parents. About 10 years ago, Jim purchased a 102-acre parcel with a mountaintop site with 100-mile views. He moved up a single wide trailer to live in. “You hauled that trailer up that driveway?” someone asked incredulously. Oh, no, there was no driveway back then, and airlifting it in seemed silly. “We pushed it up the side of the mountain with a front end loader,” Jim says with a grin. Like many homeowners with a vision, Jim sketched the house on a piece of scrap paper, first the prow front all glass west and south facing structure, then the fireplace and stone staircases.

He wanted an all natural, locally-sourced stone chimney three floors high with curving stone staircases behind two fireplaces going from the open lower level to the first floor and then to the second story master suite, plus a stoned section behind the lower level fireplace for a woodstove and another one on the second story. Plus lighting. And three electrical outlets. Jim called in his ol’ buddy Conroy who looked at the rough sketch and confidently declared: “Sure, I can do it.”

Planning

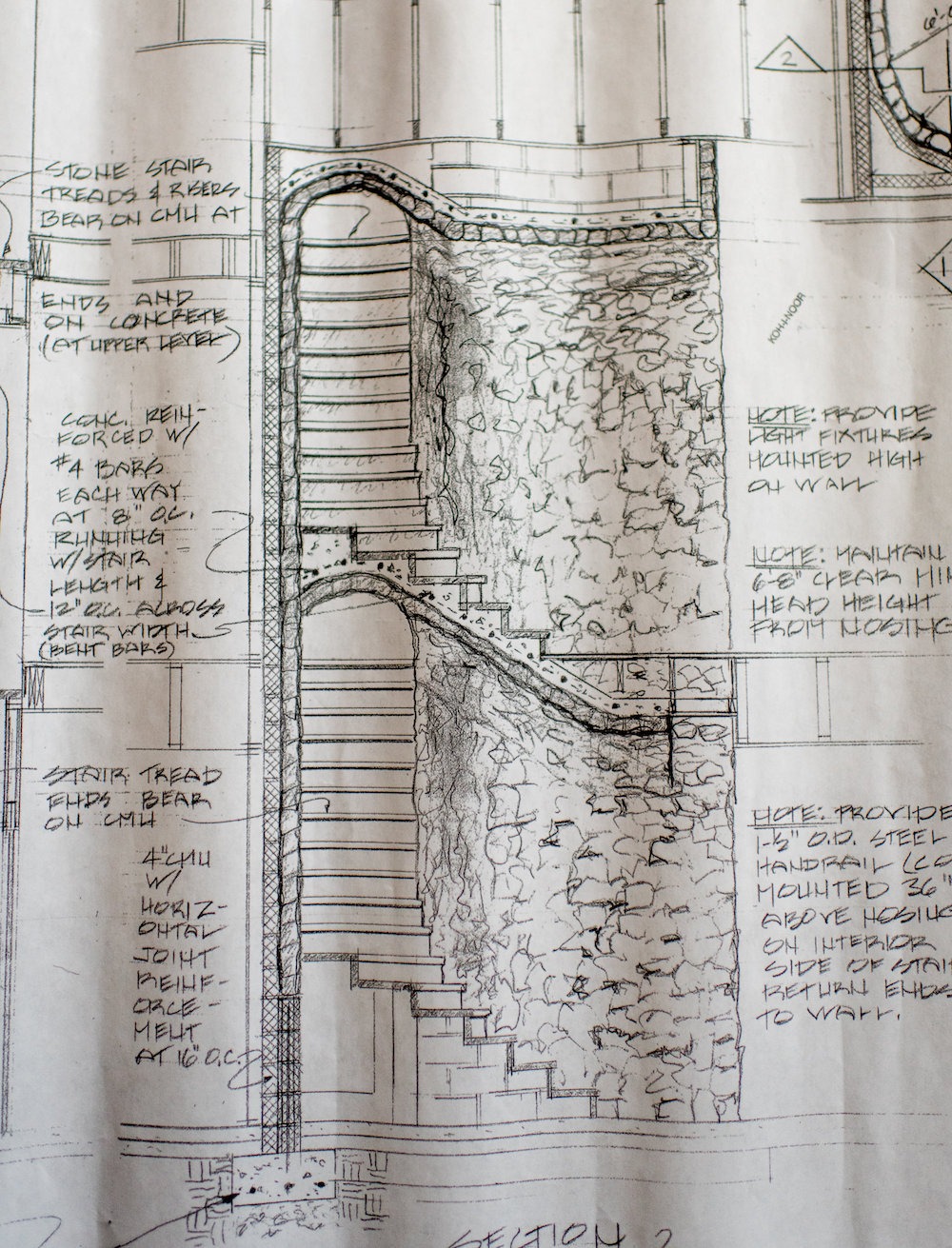

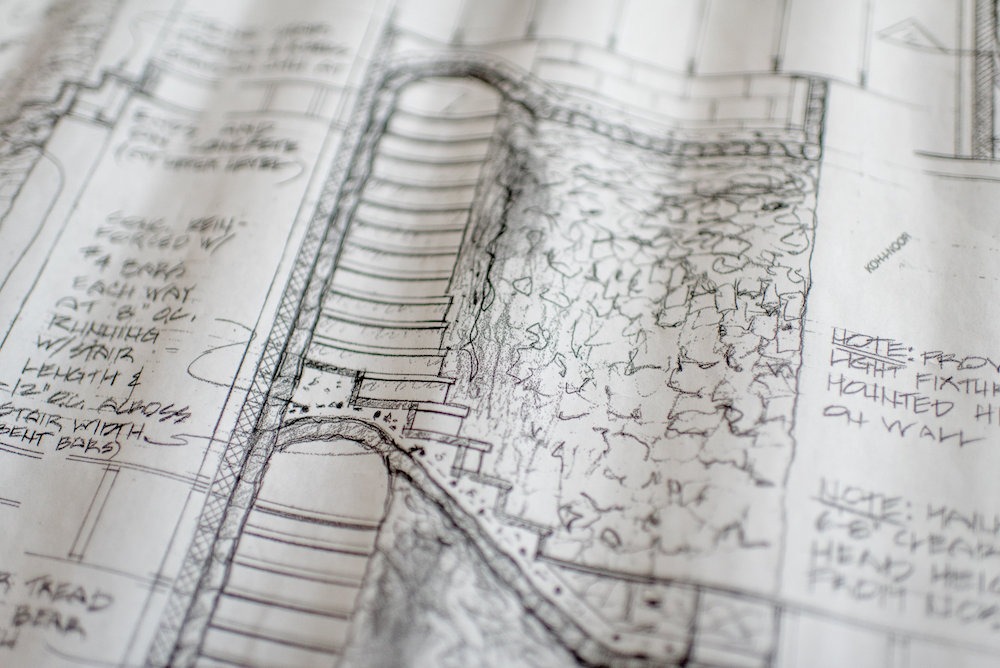

The mantra for prime real estate might be location, location, location, but for a stone project of this magnitude, it is: Planning, planning, planning. Though Jim’s property is not inside any incorporated town limits, there’s a county with building regulations and approval processes for home construction. The powers that be over there don’t work well with sketches on scrap paper, so Conroy took the vision to an architect. “Getting the drawing and approval was the first step, so I went to Z. Van Coble, a licensed architect and assistant provost for academic space at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.”

Coble remembers the project. “The great challenge was being code compliant in terms of height and width,” he explains. “You need 6 feet 8 inches of clear height and clear width of 36 inches. This was a tight floor to floor height, and the stones would take up some of that vertical space.” Reluctant to be the only one sealing the document, Coble suggested a second set of eyes and expertise. Conroy brought in Mike Fitzgerald, a structural engineer with Balzer and Associates. The firm, founded in 1967, has five offices throughout Virginia offering complete services in a wide range of architectural, civil engineering, structural engineering and environmental applications.

“He had some great input,” Coble continues, “including how to support the stone arch overhead

which was shallow.” Thus, the stone arch stairway ceiling has concrete and steel rebar above itwhich is supported by the CMU behind the stone sidewalls, creating sort of a monolithic structure. “It was certainly the most unique stone and concrete structure I’ve worked on,” adds Fitzgerald. “In fact, I still have that drawing on the wall in my office.”

It’s possible that Conroy’s confidence all along the way tipped the scales in his favor. Once the county officials had the drawing, they made a change order to the blueprint for the building permit, which originally had a simple fireplace. Then, it was full steam ahead for this stone mason to embrace a once-in-a-lifetime kind of project.

Building

The chimney and fireplaces were constructed first, starting with the lower level hearth with its two cantilevered stone benches flanking the fireplace opening. The main level fireplace was next and on up through the roof. “The whole thing rests on bedrock, and we estimate it weighs some 150 tons,” says Michael Bailey, Conroy’s lead mason and right-hand man. The entire project consumed 120 tons of stone, which was all hand-picked, loaded, transported and unloaded by Conroy and his crew of three more men. “Giles County [Virginia] is well-known for its sandstone in terms of quality and color,” Conroy states. Having a private source in a ravine in an undisclosed location with landowner permission was a huge bonus. They hauled all the rock in Stone Age Masonry’s 1979 Ford F-450, 4WD, red truck which Conroy bought new off the showroom floor. The company has two other trucks, and each of them is red, a flamboyant touch to the business image.

The rock was dumped outside the still open framed house, then loads were driven into the basement in a Bobcat T190. Bailey has been working with Conroy for 17 years, and he recalls: “The whole room was a big rock pile. We set up two stone tables, two by three feet each to work on; there’s no way any of us wanted to break our backs splitting and facing rocks on the floor for six months.”

After the fireplaces were in, frames for the staircases were constructed. “Before starting anything, I had to figure out where every stair tread would be. We’re only permitted a 3/8″ variance on the stair riser, and we needed to plan the lighting.” Conroy drew the plan on a wall in the open, unfinished basement where the staircase construction commenced. They built a wood arch out of 3/4-inch plywood with radius cut at the top and a wood 2 x 4-inch wall on each side, then laid everything in sand first.

“Once you have the forms in, you can’t get back in there, so everything has to be planned precisely,” Conroy states. “The lights needed to be equally spaced at the right heights in the staircase wall.” All the electric wires are encased in 1/2″ PVC pipe for conduit, which they designed and installed as they went along. There are 3-way switches at the top and bottom of the staircases. The second staircase was just as challenging as the first one.

It’s hard to know if the county was enthralled, challenged or simply annoyed with such a unique building project, but officials showed up every step of the way. They seemed to come all the time, checking all the arch forms, checking rebar in the concrete, making sure the stair treads were the right height and everything else. Not surprisingly, Conroy passed every visit and every milestone with his characteristic confidence and high quality skills.

Finishing

The rocks have not been polished smooth and some still have lichen attached to represent the most natural appearance. To pass code, the stair treads are Pennsylvania Bluestone, an attractive sandstone found predominantly in northeastern Pennsylvania, as well as small sections of New Jersey and New York. It is an amalgamation of mica, sand and feldspar and must be cut precisely along its horizontal layers. It is a durable stone, resistant to cracking. Conroy placed a handsome band of bluestone around the chimney above the roof line. The stainless steel railing is yet to be installed and will need to be in place for an occupancy permit.

The house is one of those lingering projects that proceeds as the homeowner’s revenue stream permits. Tannahill, who is serving as his own contractor, has a successful business. Tannahill Truck and Bus Repair, Inc., is located at exit 109 off Interstate 81, and he is admittedly as busy as he can handle. The retreat of his mountaintop is a welcome scene every evening from which he can see a hundred miles as well as close in should anyone venture up the winding, 3/4-mile, crunchy dirt driveway.

Of course, a common question is the price of this stone work, and the responses of Conroy and Tannahill are similar for their analogies. “You could buy a nice small home in the county, even with the discount,” Conroy offers. He gave the homeowner a family discount, since he’d done work for Tannahill’s dad previously. “Oh, you could purchase a big house with some acreage in the county when you factor in the cost of the glass, which was required to be set in steel casings and rated for 120 mph wind,” Tannahill adds. And while Conroy may have finished with this stone fireplace and staircases, he is far from done at the house. He is currently working on laying tile in the master bath, which is an extravagant space with gray swirl tiles on the floor, lower walls and tub surround.

So, while Tannahill may not have chosen the build site or the spiral vaults [aka staircases] to ward off enemies like in the days of castle construction, he did provide one stone mason with a project which challenged his skills, creative mind and passion for rock work. Like many a visionary artist with an innovative streak, David Conroy could see the final result in his head before picking up the first stone. He knew these stone staircases hugging massive stone fireplaces were not-so-impossible. In fact, he proved it.

Words: Joanne M. Anderson

Photos: Kristie Lea Photography

Additional Photos: Courtesy of Z. Van Coble

Joanne M. Anderson is a freelance writer, magazine editor and frequent contributor to Masonry Magazine. www.jmawriter.com.

SIDEBAR:

Rock: 120 tons

Crew: 4 men

Build Time: 6 months

Overall height: About 40 feet

Mantle main floor FP: 8 1/2-foot single rock, polished on top, one ton

Concrete: Roanoke brand Portland straight type 1

Stair Treads: 32 total

Keystone: rock from Jim’s dad’s project 20 years ago, “two ridges over” [location]

Materials: “All God made except stainless steel and glass” [homeowner Jim Tannahill]

Price Tag with discount: $70,000

Forever Stone Staircases: Priceless