As you’ve learned from our Marvelous Masonry series, the structures created through the trade have a rich history and have stood the test of time. However, not all historic masonry is outside of the United States. In fact, one of the most storied buildings in the industry is based right in our nation’s capital, Washington D.C. The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington, also known as the Washington National Cathedral, has been a focal point of faith for our country throughout the years.

The sixth largest in the world, the Washington National Cathedral’s construction started nearly 110 years ago in 1907. Then-president Theodore Roosevelt laid the cornerstone on September 29, 1907 and kicked off construction. However, likely no one assumed that the project would only be completed another 83 years later to the day.

Filled with rich history  and years of hard work and manpower, the MCAA and Masonry had the privilege of touring the Washington National Cathedral with Joe Alonso, Head Stone Mason of the building and Jim Shepherd, Director of Preservation and Facilities. Thanks to Joe, Jim and everyone at the cathedral for giving us the opportunity to share information on this American Treasure with our readers. For more detailed information on the Washington National Cathedral, please visit their website at: www.cathedral.org.

and years of hard work and manpower, the MCAA and Masonry had the privilege of touring the Washington National Cathedral with Joe Alonso, Head Stone Mason of the building and Jim Shepherd, Director of Preservation and Facilities. Thanks to Joe, Jim and everyone at the cathedral for giving us the opportunity to share information on this American Treasure with our readers. For more detailed information on the Washington National Cathedral, please visit their website at: www.cathedral.org.

The History and Construction

The idea behind the Washington National Cathedral came about during the time of our first President. The year was 1791, and George Washington worked with Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a military engineer who worked on the basic plan for Washington D.C., to envision a “great church for national purposes” to be used by everyone and not any particular religion or denomination.

On January 4, 1792, President Washington’s plans for D.C. ran in The Gazette of the United States, Philadelphia. The site that was originally intended for the church, Lot D, eventually became The National Portrait Gallery. It would eventually take about a century for any further developments on the church.

In 1893, the US Congress issued a charter and incorporated the Protestant Episcopal Cathedral Foundation of the District of Columbia, which allowed the construction for the place of worship and institutions of higher learning. In 1896, a new location was chosen for the cathedral, approximately four miles northwest of the original choice. Mount Saint Alban would serve as the site for the structure, which at 400 feet above sea level would cement the project’s place as a focal point for the city.

It wouldn’t be until September 29, 1907 that then-President Theodore Roosevelt laid the first stone for the project. Part of the stone was sourced from a location near Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus Christ, for symbolic purposes. The stone was placed into a larger piece of American-sourced granite, and inscribed is the Biblical verse “The Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.”

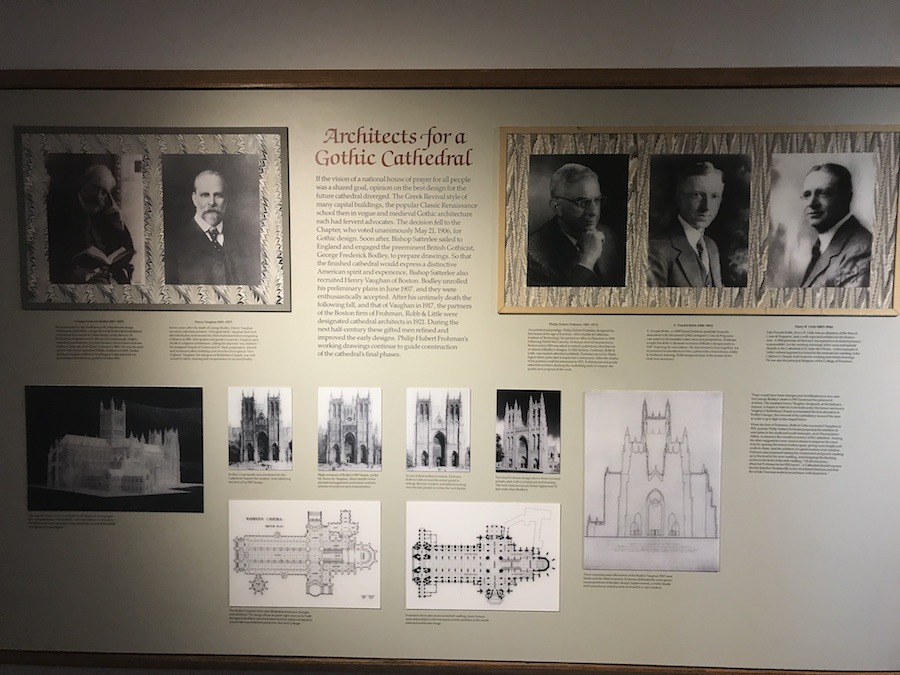

With a project that took 83 years and cost an estimated $65 million, the Washington National Cathedral was clearly built to last. With a total weight of 300 million pounds and constructed in the English Gothic style of the 14th century, one fact that may surprise our readers is that the structure does not use steel supports. Instead, artists, sculptors, and stone masons were brought in to achieve the classic look in a more modern era.

Instead, artists, sculptors, and stone masons were brought in to achieve the classic look in a more modern era.

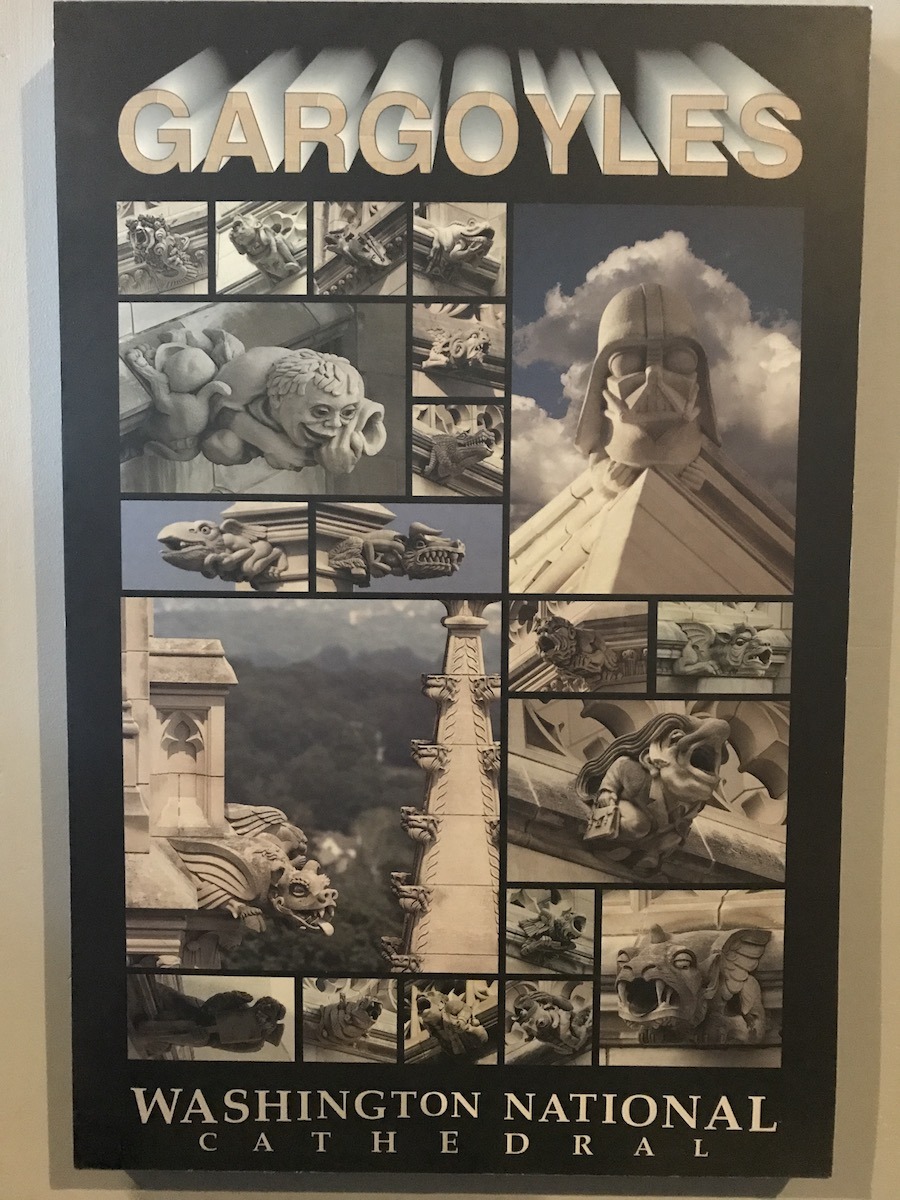

Built in the shape of a cross using Indiana limestone, the exterior of the cathedral features flying buttresses, intricate carvings,  high arches, 112 gargoyles (including one in the shape of Darth Vader), and gutters large enough to walk through. The cathedral rises over 300 feet, and spans over 500 feet in length.

high arches, 112 gargoyles (including one in the shape of Darth Vader), and gutters large enough to walk through. The cathedral rises over 300 feet, and spans over 500 feet in length.

Built with private funds and receiving no money from the federal government nor the National Episcopal Church itself, construction had to be completed in phases over the past 83 years. The first part of the cathedral that was built was the Bethlehem Chapel, which still offers services to this day. It was placed atop the foundation stone at what is now considered the crypt level of the building.

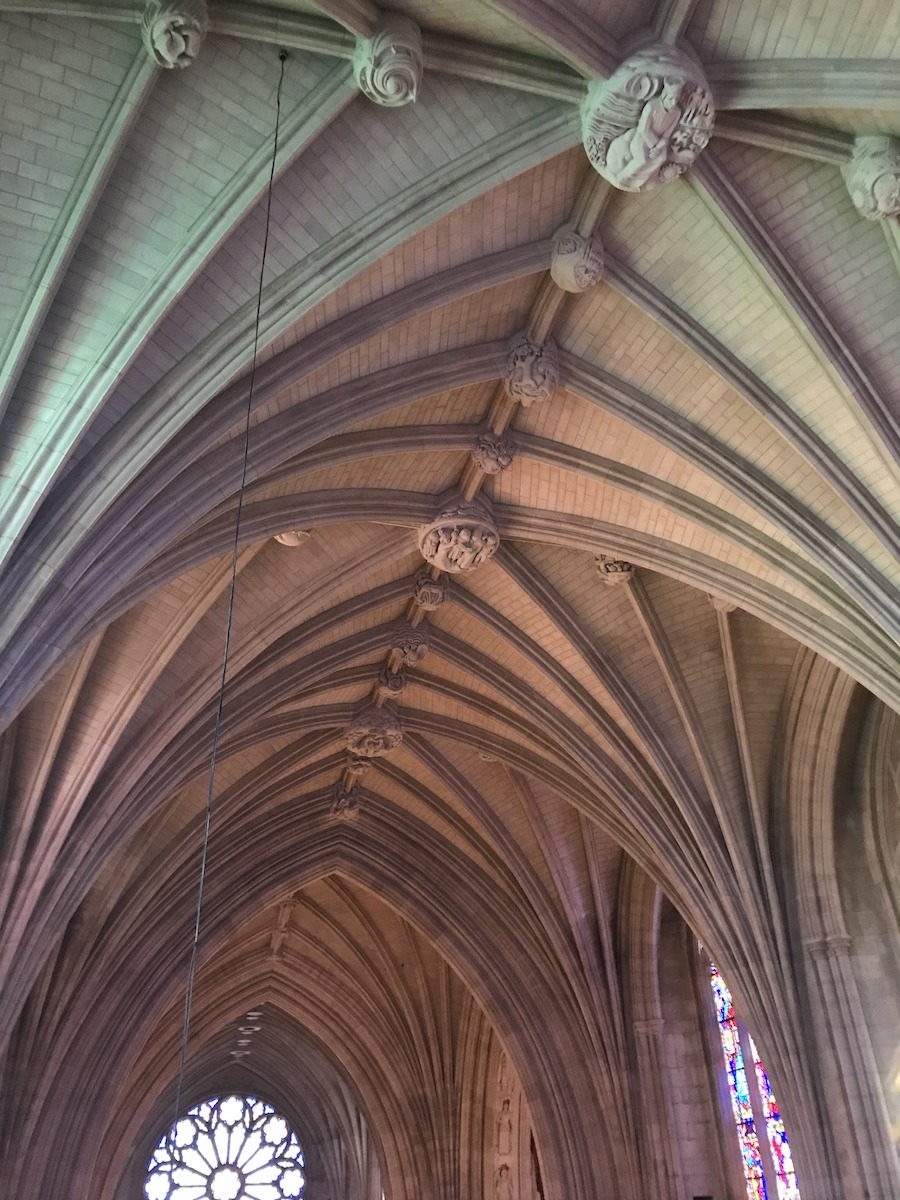

The interior of the structure features a Medieval-inspired labyrinth designed to replicate the one in the nave of France’s Chartres Cathedral. Additionally, seven-story vaulted ceilings are a significant feature of the structure. Designed to transmit the weight of the roof and walls into the stone piers, the ceiling arches are capped by over 762 boss stones throughout the structure.

The work would eventually be completed in 1990, exactly 83 years after the date that the work first begun. Then-President George H.W. Bush attended the ceremony that saw the final finial placed on the west towers of the cathedral.

After its completion, the National Cathedral has hosted a variety of events and remembrances. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the cathedral held a National Day of Prayer and Remembrance Service on September 14, 2001. In 2004 after the death of former President Ronald Reagan, the cathedral was the site of his state funeral. Three years later in 2007, former President Gerald Ford’s state funeral was also held there. In 2009 and 2013, the church held the respective national prayer services for then-President Barack Obama. It has since hosted the national prayer service for President Donald Trump in 2017.

While the cathedral’s first few decades post-completion have been studded with several solemn and historic events, one in 2011 put the structure (and the masonry) to the test. The day was August 23, 2011, when a rare 5.8 magnitude earthquake struck at 1:51 pm.

The Earthquake

With an epicenter within the Piedmont area of Virginia, the quake is tied as the largest of its kind within the United States East of the Rocky Mountains. It caused several aftershocks of up to a 4.5 in magnitude, and was felt in over 10 states and neighboring Canadian provinces. Thankfully, only minor injuries and no deaths occurred as a result of the earthquake, but major damage was done to several buildings in the metropolitan area.

Unfortunately, the cathedral was one of those buildings. Several witnesses reported seeing elements of the structure shaking, twisting, and falling, according to Joe Alonso. He estimates that had the earthquake gone even seconds longer than the less-than-a-minute time it did, the damage could have been absolutely catastrophic both for the structure and those in and around the cathedral.

According to estimates, the destruction caused ranged from the $25 million to $34 million mark. On the cathedral’s website, the damages from the quake are highlighted.

On the Central Tower:

- The four grand pinnacles of the central “Gloria in Excelsis” tower rotated. Each grand pinnacle is over 40 feet tall, weighs about 50 tons, and is topped by a four-foot-tall grand finial that weighs about 500 pounds. Three of the four grand finials fell to the tower’s roof; the top five courses of stone were shaken badly.

- Additional smaller pinnacles atop the tower were badly damaged.

On the South Transept:

- Dislodged stone struck a gargoyle and “decapitated” it. The gargoyle’s head was held in place only by the drainpipe that runs through the gargoyle to expel rainwater.

- One grand pinnacle was so damaged that it cannot be removed until funds are in place for its restoration. It will remain encased in scaffolding until it can be repaired.

On the North Transept:

- The grand pinnacles were so destabilized that workers could gently rock them back and forth on their bases.

- Several pinnacles skipped up and rotated like spinning tops, and several slender pinnacles collapsed entirely.

Flying Buttresses:

- The six freestanding flying buttresses of the east end—the oldest part of the cathedral—swayed or moved, causing the flying buttress arches to stretch and move, resulting in cracking and separation of stones from one another.

- When construction began in 1907, there was no reinforcement used between stones. The seismic motion caused stones in the buttresses to shift and separate, and loosened and rotated the pinnacle stones.

- Rotation and movement along almost every exterior pinnacle on the cathedral caused hundreds of spalled corners and stones (stones that have crumbled or flaked off), cracks, and fallen crockets and finials, requiring re-carving.

Immediately following the earthquake, the cathedral shut down from the Tuesday of the Earthquake to the Saturday of that weekend. A “Difficult Access Team” from the cathedral’s engineering firm was brought in to rappel along the cathedral and assess and document the issues that had occurred. Additionally, the in-house team, led by Joe Alonso, was brought in to assess the damage. After its completion, the repair and restoration work was broken into three phases: Immediate, Phase I, and Phase II.

Restoration Work

Immediately after the earthquake, the team primarily focused on securing the building and planning for future repairs. An added challenge was that the cathedral would remain open during the repair process. After the seismic event, cathedral leadership was able to raise around $2 million for the immediate repairs that would make the structure safe enough for the many visitors to enter the building.

Crews first installed 65 feet of scaffolding above the nave floor. This allowed crews to examine the vaulted ceilings and boss stones and provide any necessary cleaning. Falling debris would be caught through the installation of netting.

Outside the cathedral,  the flying buttresses were the first place teams went. As the original buttresses did not have suitable reinforcement, teams drilled into them and installed steel rods around 25 feet in length. They were placed diagonally along the buttresses to provide stability in the event of another seismic event. Any pieces that fell or were shaken loose from the rooftops were secured, and many still sit in the same spot to this day.

the flying buttresses were the first place teams went. As the original buttresses did not have suitable reinforcement, teams drilled into them and installed steel rods around 25 feet in length. They were placed diagonally along the buttresses to provide stability in the event of another seismic event. Any pieces that fell or were shaken loose from the rooftops were secured, and many still sit in the same spot to this day.

Phase I  of the restoration was funded by another $8 million, and concluded in June of 2015. The interior of the building looks like it never has before, with boss stones resembling what their original form. Decades of buildup were removed. Once again, the cathedral was safe for visitors. However, there is much more work to be done.

of the restoration was funded by another $8 million, and concluded in June of 2015. The interior of the building looks like it never has before, with boss stones resembling what their original form. Decades of buildup were removed. Once again, the cathedral was safe for visitors. However, there is much more work to be done.

Jim Shepherd, the cathedral’s Director of Preservation and Facilities, estimates that even after the completion of the phase, there is still well over 85% of work left to do. Cracked buttresses need reinforcement, damaged and destroyed stonework needs to be recarved, the hand-carved finials of angels still aren’t at the tops of certain points of the building, and one decapitated gargoyle needs to be repaired of replaced.

The Central Tower’s scaffolding, still up to this day, is merely there to make sure that the building is safe. Currently, no active work is being done on that portion of the building until the necessary funds have been raised to complete the work.

Phase II of the project is going to be significantly costlier, with the cathedral’s own estimate being over $20 million. As such, this phase will take much longer than the first. The second phase of the project is so expansive that it has been broken into nine sub-phases with an approximate cost affixed to each one.

Per the cathedral’s website, they are:

- North Transept Façade (est. $1.2M): Repair the engaged buttresses and pinnacles on the façade of the north transept, enabling removal of scaffold protection at the entry to the Cathedral’s Administration Building. Summer 2016 completion.

- West Towers (est. $350K): Repair miscellaneous pinnacle damage at the tops of the two west towers.

- North Transept Buttresses (est. $1.6M): Repair and reinforce the engaged buttresses and pinnacles on the north transept not covered by the work in Part A.

- North Nave (est. $3M): Repair all engaged buttresses and pinnacles along the north nave.

- South Nave (est. $2.9M): Repair all engaged buttresses and pinnacles along the south nave.

- South Transept (est. $4.7M): Repair engaged buttresses, severely damaged grand pinnacles and damaged smaller pinnacles on the south transept façade.

- Great Choir South (est. $2.5M): Repair engaged buttresses and pinnacles; clean and repoint masonry.

- Central Tower (est. $3.3M): Recarve portions of the four central tower grand pinnacles and restore remainder of center tower secondary pinnacles in order to remove very visible stabilization scaffold.

- Garth (est. $3.6M): Repair and reinforce engaged buttresses and pinnacles around garth garden so that it can be reopened.

Conclusion

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed that the “work begun this noon.” However, it’s debatable whether or not anyone expected the work to take another 83 years. By the same token, it’s arguable as to whether President George H.W. Bush knew that in 1990, the “work completed this noon and the new work yet to begin” would include a significant amount of restoration and repair in the wake of a natural disaster.

The National Cathedral, even with the exception of the stabilization needed in the wake of the earthquake, is a testament to both the strength of masonry to stand the rest of time. Additionally, it’s proof that though there’s much to learn from the amazing structures around the world, we have our own American Treasures right in our own backyard.

Editor’s Note: We hope you enjoyed reading about the history and construction of the Washington National Cathedral. I know we all enjoyed the tour of the breathtaking building, and appreciate all the sweat equity that went into making it the majestic focal point of faith that it has become. Do you have any other National Treasures you’d like us to highlight? If so, send them our way and we’ll do our best to get them into an upcoming issue of Masonry.