From Egypt last month, we now move up to the Czech Republic in Central Europe. As with most European countries, it has an amazing history including being part of various empires. During World War II, it was part of Czechoslovakia. However, Czechoslovakia was peacefully dissolved in 1993 and the independent states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia were formed. In the past year, the country has adopted the short name of Czechia in addition to the formal name of Czech Republic.

Czechia is one of Europe’s 16 land-locked countries (Figure 1). In size, it is slightly smaller than South Carolina but with more than double the population (10+ million). It is ranked 6th in the world as a peaceful country (the US is ranked 103).

Figure 1- Central Europe (Credit: goldyg/Shutterstock.com)

Figure 1- Central Europe (Credit: goldyg/Shutterstock.com)

Despite its size, Czechia (Figure 2) has 12 UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage sites and another 19 that are being considered for designation. A common thread throughout these sites is masonry! Let’s visit some of these.

The most famous city is the capital of Prague (#1 on the map). The city is a gem of Europe. There are numerous historic buildings throughout Prague which was mostly spared during the war except for one bombing in 1945 by Americans with malfunctioning radar who thought they were over Dresden, Germany. Film makers have used Prague (Amadeus, Mission Impossible, Les Miserables, and xXx to name a few) for its beauty, historic sites and low cost.

Figure 2 – Czech Republic (Credit: pavalena/Shutterstock.com

Figure 2 – Czech Republic (Credit: pavalena/Shutterstock.com

Since 2010, I have been fortunate to be an invited lecturer at the Czech Technical University (CTU) in Prague as part of an international advanced masters course in Structural Analysis of Monuments and Historical Constructions. My primary topic is repair and strengthening of masonry structures. During this time, I have able fortunate to visit numerous historic sites and work with students on the evaluation and restoration of various projects.

Figure 3 shows the St. Vitus Cathedral on the hill in Prague within the walled area of the Prague Castle. This UNESCO site has to be the highlight of any visit to Prague. The Gothic construction was begun in 1344 and wasn’t completed until 1929! There were wars and changes in government that caused the construction to stretch out nearly 700 years.

Figure 4 shows a Google Earth view of the castle (white outline) with the cathedral. Figure 5 shows an enlargement of the cathedral. Anyone can take a virtual tour of the castle from the web site https://www.hrad.cz/en/prague-castle-for-visitors/virtual-tour.

Figure 4 – Prague Castle with cathedral (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 4 – Prague Castle with cathedral (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 5 – St Vitus Cathedral (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 5 – St Vitus Cathedral (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Like many of the cathedrals of Europe, St, Vitus is an amazing masonry structure with its flying buttresses and soaring towers. While Gothic, it has touches of other influences due to the length of construction. Figure 6 shows the south side of the cathedral which was constructed from the right to left. We see the original entrance in Gothic style from the 1300s (a), Renaissance tower from 1409 (b), and Baroque top rebuilt 1600s (c). There are also Romanesque elements that were introduced after a fire in 1541. The current western entrance and towers (d) were the last portion completed (1929).

Figure 6 – St Vitus, South side

Figure 6 – St Vitus, South side

Figures 7 and 8 show interior views of the marvelous masonry construction of St. Vitus. The stone is primarily sandstone and the original stone joints from the 1300s are filled with lead, not mortar. There are no records as to why they used lead. Many believe the builders were concerned about high compressive loads from the stone weight. Imagine no repointing in over 700 years! The 20th century construction at the west end used lime mortar.

Figure 7 is the view every tourist gets. Notice the iron bars tying the arches together. Throughout Europe you will see some roof arches with ties and many without. This building is a bit unusual in that it has both tie bars for the arches and flying buttresses on the exterior.

Figure 8 is taken from an elevated part of the cathedral that is not open to tourists. I was fortunate to be given a VIP tour of the building arranged by my Prague colleagues through the office of the President of the Czech Republic. This was very special because the professors who went on the tour had lived in Prague their entire lives and never had this opportunity.

Figure 7 – Interior of St. Vitus

Figure 7 – Interior of St. Vitus  Figure 8 – Interior of St Vitus

Figure 8 – Interior of St Vitus

The historical city of Prague (Lesser Town) is on the same side of the river as the castle. Walking down the hill from the castle, you’ll find numerous stone buildings, churches and government offices. On the way, you pass one of the student work sites (Figure 4, red oval; Figure 9). This building was used as a case study to evaluate masonry, timber and material restoration.

Constructed after a fire in 1541 that destroyed the previous house as well as damaging much of the castle, this building has had many uses but is most well known as a Theatine monastery. Despite the building’s age, written records were available that documented its major renovation campaigns. There is a pattern of significant work every 100-125 years; only possible with masonry buildings. Since 2012, it has been undergoing another restoration and renovation into a hotel.

The monastery was constructed with both sandstone and Opuka, a locally available marl. Opuka was plentiful and used throughout Prague. However, its low quality has created enormous restoration problems. Replacement stone is available in small quantities but often it is simply replaced with sandstone.

Figure 9 – Theatine Monastery (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 9 – Theatine Monastery (Courtesy of Google Earth)

Figure 10 shows one side of the building; the Opuka stone is covered with a rendering (plaster). Below several windows, cracks in the underlying stone have been stitched. Figure 11 shows the stitching before the rendering was completed. Helical rod was used. This procedure was used throughout the exterior. In the US, stitching cracks in brick walls is common, but it can be done in stone as well. While steel rods are normally used, a thin cable is often placed in the irregular joints of ashlar stone.

Figure 10 – Theatine Monastery

Figure 10 – Theatine Monastery

Figure 11 – Close-up of stone stitching

Figure 11 – Close-up of stone stitching

Figure 12 show an interior arch with stitching also. These were used instead of through anchors.

Figure 12 – Interior arch stitching

Figure 12 – Interior arch stitching

As the St. Vitus Cathedral was under construction, Charles IV began a building spree. He engaged the cathedral architect for several other projects including the Charles Bridge (Figure 13) crossing the Vltava River. St. Vitus Cathedral is visible in the background. The bridge opened up expansion of Prague to New Town (founded 1348) across the river from the castle.

Begun in 1357, the bridge was originally called the Stone Bridge (constructed of sandstone) and was renamed the Charles Bridge in 1870. The bridge was preceded by a 21 arch span stone bridge that collapsed in 1347 (built 1158) due to flooding. Another UNESCO site, the Charles Bridge has 16 spans of between 50 to 70 feet. There are large stone towers at each end to symbolize Prague’s growing power and influence at the time they were built (Figure 14). In 1978, the bridge was converted to a pedestrian way and is always one of the busiest spots in Prague. The 30 Christian statues that adorn the bridge above the arch piers were added in the 1700s; they are now replicas.

The river has a long history of almost yearly flooding that has damaged the bridge several times, including destroying some arches. Each time the bridge was repaired or rebuilt. On March 4, 2017, 50,000 people were evacuated from the historical area of Prague as well as many other riverside cities.

The most recent restoration was begun in 2008. In 2010, UNESCO criticized the quality of the work stating “the restoration of Charles Bridge was carried out without adequate conservation advice on materials and techniques”. Critics felt that original features were being removed and replaced unnecessarily. So, even in Europe with a long history of preservation, there are disagreements over methodology just as we have in the US.

Figure 13 – Charles Bridge (Courtesy: trabantos/Shutterstock.com)

Figure 13 – Charles Bridge (Courtesy: trabantos/Shutterstock.com)

Figure 14 – Charles Bridge, East tower (c.1358)

Figure 14 – Charles Bridge, East tower (c.1358)

Moving on into Old Town (founded 1348), we find more and more examples of marvelous masonry. Get an aerial view of this area and more of Prague at http://www.charming-prague-hotels.com/articles/prague-views-and-towers.

In 1348, New Town was first surrounded by a fortification wall and towers (Figure 15). Masonry was always the choice! Much of these brick and stone walls still exist.

Figure 15 – Fortification Walls

Figure 15 – Fortification Walls

A main visitor attraction is the Old Town Square. Any direction you turn, you’ll be amazed at the masonry structures. Figure 16 is the sandstone north elevation of the Old Town Hall from 1364. It is one of the most famous tourist spots in Europe because of the astronomical clock and calendar clock on the east elevation (Figure 17); the masonry ornamentation is amazing as well. The clock was added in 1410. Tourists mob the area to see moving statues come out above the clock each hour.

Figure 16 – Old Town Hall (c. 1364)

Figure 16 – Old Town Hall (c. 1364)

Figure 17 – Astronomical clock

Figure 17 – Astronomical clock

Looking north from the clock tower, we see the Church of Our Lady before Týn (begun c.1365 and completed 1511). The sandstone Gothic church (Figure 18) has spires over 260 feet tall. Legend has it that this church gave Walt Disney the inspiration for the Sleeping Beauty Castle. It is surrounded by other buildings and finding the entrance can be a challenge.

To this day, the Tyn church along with most churches from its era, remain unheated. Thermal mass is very useful in summer to maintain a cool interior temperature, but a winter visit can be bitterly cold. Plan to sit near a portable infrared heater and still be cold.

Figure 18 – Church of Our Lady before Týn (c. 1365)

Figure 18 – Church of Our Lady before Týn (c. 1365)

The number of masonry sites in Prague you could visit is amazing, but let’s look at a couple newer examples. Figures 19 and 20 show the Sacred Heart Church (1929-1932). The unique brick construction is topped with a white cast stone. The building has been nominated for UNESCO monument recognition as part of the body of work by the architect, not as a singular structure.

Figure 21 shows a close-up of the oculus with the Czech Republic’s largest church clock. For some reason the architect chose to construct the oculus with concrete and face it with brick. Thermal effects, concrete shrinkage and brick expansion have resulted in masonry cracking of the oculus. Several previous repairs have been unsuccessful; the oculus is being monitored and modeled before starting another repair.

Figure 19 – Church of Sacred Heart

Figure 19 – Church of Sacred Heart  Figure 20 – side elevation

Figure 20 – side elevation

Another more modern building is shown in Figure 22. It houses the Architecture Department at the Czech Technical University (built 2011). This concrete frame building has an exterior cavity wall of clay tile infill with brick veneer. I work a couple buildings away in the Civil Engineering building.

Figure 22 – Architecture Department, CTU

Figure 22 – Architecture Department, CTU

The reason for mentioning this building is highlighted in Figure 23. The veneer was constructed while I was back in the US. Seeing it for the first time in 2012, I was taken by the lack of movement joints. I had to almost get within touching distance of the building to notice there were movement joints but they were zipper shaped. These are rarely used in the US due to difficulty and cost. On this building they are expertly done. The sealant color match is perfect; only the thickened joint gives it away. I have been watching this building for five years now and there has been no splitting of the sealants.

Going back to historical masonry, let’s take a look at the Summer Palace of King Ferdinand II (Figure 24). This building was constructed in 1698 as a hunting retreat for the king in the Baroque style.

Figure 24 – Historical drawing of Palace

Figure 24 – Historical drawing of Palace

It became a restaurant in 1820s and remained one of the finest in Prague until 1968. At that time, the Communist government nationalized this and many other buildings in the country.

In the 1850s, the building was transformed into a Neo-Gothic structure with numerous additions and modifications (Figure 25). The main interior still maintains the baroque appearance. The loadbearing walls are constructed of Opuka. All the exterior walls are rendered with a lime plaster.

Figure 25 – Summer Palace (2010)

Figure 25 – Summer Palace (2010)

The front arcade was added using brick vaulting for the roof and the exterior spandrels (Figure 26). The columns of the arcade are constructed of Opuka and some brick. In the vaulting, a wrought iron tie rod was embedded into the brickwork at each rib to connect the exterior columns supporting the newer vaulting back to the existing building. Water penetration from the roof deck has corroded the tie rod and spalled the plaster rendering as visible in the photograph.

A longitudinal crack runs along the length of the arcade (see dashed line). Analyses indicated this crack was based upon the original construction. Restoration plans include new waterproofing on the roof deck and repairs to iron rods.

The restaurant closed after being nationalized in 1968 and has fallen into disrepair. The grounds of the hunting retreat have been transformed into an English park. Since 2007, the city has been slowly trying to save and restore the building. Figure 27 shows the building surrounded in scaffolding covered with a wrap that depicts the appearance proposed after restoration. Many European cities use the wrap strategy to stimulate public interest in a restoration by showing what could be. In the US, you may remember the scaffolding of the Washington Monument was similarly wrapped during its restoration.

Figure 27 – Palace (2014) under wrap

Figure 27 – Palace (2014) under wrap

One major problem stalling restoration, other than funding, is flooding. Since 2002, the river has risen eight to 12 feet above the ground floor. Until Prague solves the flooding problem, city officials are hesitant to invest in restoration; so, most efforts have been to stabilize the building (see shoring on Figure 25) and protect the original ceiling murals inside. Prague consultants and CTU students have studied the materials extensively, modeled the masonry structure, proposed a new roof, and offered restoration plans.

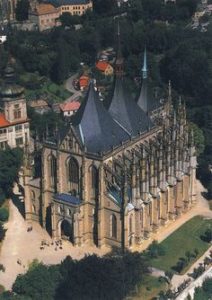

Time to leave Prague! Of the hundreds of historic masonry sites to visit, I’d like to highlight St. Barbara’s Church in Kutná Hora (#2 on the map). About an hour from Prague, the city had major silver mines and the mint for the country. I’ve been there at least four times and would go again tomorrow if I could. Plus, it is another UNESCO site.

Construction on the church (Figures 28 and 29) began in 1388. After a quick start, there was a time period of about 500 years where no work was done. For that time, the roof was not completed and it rained into the building. Imagine if you were asked to complete the construction of a building that had been sitting for 500 years and the roof was open. How much rework would you expect to be needed on the existing? Was there are protection on the walls? Ultimately, construction restarted in 1905 and was finally completed in 1908.

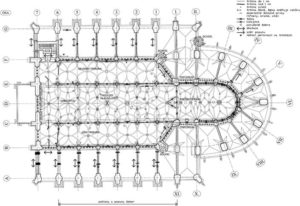

Imagine how many full generations of masons worked on this church and never saw it completed. Despite all that time, the church is only one-half the size that was originally intended. Figure 30 shows the floor plan.

The sandstone used to build the church was quarried locally. Despite being a land-locked country, the stone has sea shells that are readily visible. The marvelous masonry of the main nave (Figure 31) is braced by amazing flying buttresses.

Even though the church was begun in 1388, the buttresses are likely some of the last elements to be constructed making them just over 100 years old. From 2003 to 2011, the recent restoration needed to strengthen several buttresses and interior arches that had cracked and spread from thermal stresses and overload.

Figure 28 – St Barbara Church, Kutna Hura (2012)

Figure 28 – St Barbara Church, Kutna Hura (2012)  Figure 29- Credit: worldonpostcards.blogspot.com

Figure 29- Credit: worldonpostcards.blogspot.com

Figure 31 – Underside of nave roof

Figure 31 – Underside of nave roof

A flying buttress is a delicate structural element. It has two major components, a) the diagonal element which is often a shallow arch and b) the vertical pier. As seen in Figure 32, the weight of the roof causes the arch to spread putting the diagonal in compression. That diagonal remains in compression provided there is sufficient mass of the vertical pier to resist it from overturning.

Figure 32 – Graphic of flying buttress (Credit: architecturecourse.org)

Figure 32 – Graphic of flying buttress (Credit: architecturecourse.org)

For the flying buttress restoration, the contractor had to repoint and stiffen the vertical pier, jack open the crack in the diagonal element and fit a new stone to reestablish the compression, and tie several interior arches with iron bars. Figure 33 shows one of the iron bars after installation. The workmanship is superb.

Figure 33 – Strengthening with iron bar

Figure 33 – Strengthening with iron bar

As I said before, there are countless more examples of marvelous masonry, but it’s time to end this month’s article. I thought the last features I would show are several gargoyles. They are part of the great masonry structures all over Europe. Often they are carved stone of grotesque figures. Figures 34 and 35 are two examples. We have them in the US also and you’ve likely seen some. Ever wonder what they look like from above?

Figure 34 – Gargoyle (frog)

Figure 34 – Gargoyle (frog)  Figure 35 – Gargoyle (grotesque animal)

Figure 35 – Gargoyle (grotesque animal)

Figure 36 is one gargoyle viewed from above and we see a built-in copper gutter. This one also has modern heating wires to prevent ice buildup. Not all gargoyles have an open gutter, some have an enclosed pipe. These gargoyles are actually downspouts to divert roof runoff water away from the masonry walls that could deteriorate the mortar.

We started at St. Vitus Church at the Prague Castle and end back there with the gargoyles spitting out water on a rainy day (Figure 37).

Figure 37 – Gargoyles working a downspouts.

Figure 37 – Gargoyles working a downspouts.

If you get a chance to visit the Czech Republic and Prague, you’ll enjoy these sites and the many more examples of marvelous masonry.

Words: David Biggs, PE, SE

Photos: David Biggs, PE, SE (unless otherwise noted)