Green Building

The Role of the Sustainability Director

|

|

|

Ware evaluates plant dryer |

As companies around the globe begin to take a serious look at their environmental responsibilities, it’s apparent that a variety of ways exist to go green. Bonsal American, a division of Oldcastle Building Products, took a leap two years ago, hiring veteran Meredith Ware to lead the way as sustainability director. Following is an account of a day in the life of Ware through a typical day, as a company more than 100 years old goes green from the inside, out.

Meredith Ware walks into a Home Depot and feels completely at home; put her in a Bloomingdale’s, and she is lost and confused. Building products are her passion, but only due to a secret lurking beneath the surface, literally.

“Most people have no idea that the sidewalk they walk down every day is made of materials that single-handedly contribute to 8 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions,” says Ware. “Cement products are the silent killer, and I want the world to know this.”

Although concrete products are suited naturally for optimizing building emissions through thermal mass and reduction of temperature volatility, reducing Portland cement content is key to making concrete products better for the environment. Oldcastle and its parent company, CRH in Europe, made a huge commitment in 2010 to reduce cement in its products and practice good environmental stewardship, a $67 million investment.

|

|

| Ware leads a sustainability class. |

The concrete and masonry industries were born during a time when energy and natural resources were abundant. Fast forward 200 years: The population and atmospheric CO2 charts are climbing exponentially, and you see an earth unable to support human energy needs through dwindling fossil fuels reserves.

“My goal is not to teach everyone the intricate details of environmental policies, statistics and building programs,” Ware says, “but to give them the guidelines to make conscious decisions themselves.”

Ware spends a good part of her day helping people understand how good environmental practices are good business, and vice versa. “The companies I have worked with, large and small, always see a return on the bottom line when they begin to implement good environmental practices,” she says.

Ware recently helped convert all of Bonsal American’s diesel fuel-based plants to recycled fuel oil, a small effort that result in hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual savings and a huge carbon footprint reduction. “Nothing special needed to be done at the plants; we just simply switched fuel providers,” Ware says.

Not all green ideas pan out, though. Bonsal also looked at switching their fleet from diesel to cleaner natural gas. However, economically and logistically, it would have been difficult. Ware says that if an environmental decision doesn’t make good business sense, it will be hard to sustain in the years to come. Bonsal did, however, make smart adjustments elsewhere in the transportation system by optimizing full-load and back-load shipping; switching long-haul shipping to fuel-efficient rail cars or barges; and installing engine idling alerts on trucks. Just this year, an Oldcastle plant in Florida celebrated 1 million rail car shipments. That’s a lot of unused diesel fuel.

Ware, a LEED AP, also helps the executive team equip their divisions, such as Amerimix, ProSpec and Sakrete, with the tools they need to be a part of the industry’s transition to responsible products required by green building programs. She recently offered a LEED Green Associate class to any Bonsal employee who was interested.

“The room was packed; we had to pull in extra chairs,” says Ware. The class was attended by project managers, chemists, marketers, sales staff and VPs. And, the good news is that many of the employees continued their studies to pass their LEED Green Associate exam.

“Today, it almost a requirement in the building industry to have some sort of knowledge about how green building programs work,” Ware says. “After all, green building is the only building sector that continues to grow, despite the declining economy.”

Fast forward: How does Bonsal get products under the nose of LEED AP architects and builders? Ware spends a big chunk of her day looking at the environmental profile of each product. She constantly looks for new ways to reduce the carbon footprint of the products or offer products that allow customers to build in responsible ways. Sakrete reduced 5 percent of the carbon footprint of key products by simply altering the production method. The good news is that it is stronger, too!

“Once a company dissects what they offer their customers, they will find ways to save and improve all around,” says Ware. “These benefits are passed on to the consumers, who, in turn, are more pleased with the brand. It’s a positive regenerating cycle.”

Recycling

Much of the green product flood coming to market these days focuses on recycled content. A sustainability director knows to read these claims with an eye of caution. Ware believes that, generally, companies strive to do the right thing when including recycled content in their manufacturing process. But, sometimes, it takes more energy to make a product with recycled content than virgin materials. That said, the reduction of waste and land-filling is virtuous, too. It is a trade off that receives careful consideration at Oldcastle and CRH.

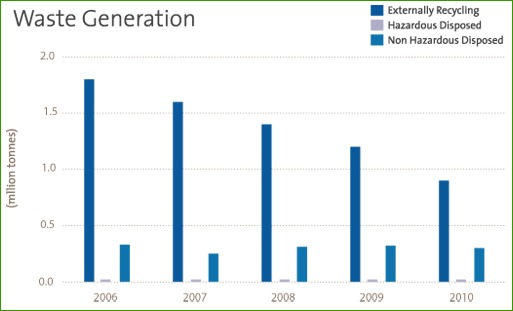

In 2010, 21 million tons of recycled material were used to manufacture their products. This was a steady increase, year after year. Also, 75 percent of waste generated at the plants was recycled, much of it internally. The company strives to reduce overall waste and has been incredibly successful.

Often, across all industries, a key waste item is overlooked: water. Water has an extremely high carbon footprint, due to sewage treatment, refining, packaging and shipping. It also is a precious natural resource that is dwindling in supply. Ware uses both “sustainability” and “director” when lecturing about water.

“It absolutely pains me to see a running faucet,” she says. “I’d rather hear nails on a chalkboard.” She constantly reminds her colleagues to be responsible. “It is as simple as maximizing mixing plant clean out water, and turning off the faucet when brushing your teeth.”

Oldcastle gets two birds with one stone as it recycles 65 percent of used water back into the company system. The company also has implemented rainwater collection systems, and reviews progress with third-party auditors annually.

There is no hiding the fact that buildings are leading contributors to the environmental plight of the planet. Although Ware admits she is overwhelmed at times with the responsibility that she and the other sustainability directors of the world face, she feels that every little step forward can lead to a big difference.

Ware began her career in Silicon Valley startup companies, and some of her former colleagues question her decision to join a corporate bigwig in an environmentally damaging industry.

“I’ve heard everything from ‘working with the enemy’ to ‘selling out’ to ‘manipulating the system,’” she says.

|

|

|

Ware conducts a green product demonstration. |

But she remains optimistic and finds inspiration through Adam Werbach, former president of the Sierra Club, who advises Wal-Mart on how to be the economic leader in environmental policies and product requirements. If Wal-Mart can do it, anyone can do it. Although Ware nostalgically believes that some of the best green ideas come out of grass-root organizations, real change cannot happen unless it does so in a big way.

“I can reduce heaps of greenhouse gasses emissions if I use Oldcastle’s organizational leverage – more so than if I try to build something from the ground up,” Ware says.

Consider this: In the United States, buildings account for 42 percent of total energy use; 67 percent of total electricity consumption; 40 percent of total carbon dioxide emissions; 13 percent of total water consumption; and 60 percent of non-industrial waste generation.

Since Bonsal American and Oldcastle are such large companies, a lot of paperwork sails across Ware’s desk. Electronic paperwork, at least. She has yet to go through one pack of printer paper in her two years working at Bonsal. A sustainability director touches all areas of a company: operations, finance, legal, human resources, marketing, research and development and, of course, public relations. Even though green declarations are coming under increased scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission, a mad rush still occurs to get green marketing out in the public eye, despite the level of accuracy. However, Bonsal American commits to only doing so when the stats are backed up.

Ware adamantly agrees with this policy: “We do not make green claims, or any claim for that matter, without being completely comfortable providing full transparency to our customers and shareholders. Bonsal’s reputation, and my reputation as a sustainably director and scientist, rides on our accuracy with these facts.”

Sustainability directors have the responsibility of organizing environmental audits and certifications, and Ware enjoys seeing the company’s statistical progress. Oldcastle spends 35 percent of its environmental investment budget tracking and monitoring progress.

“It is important to know that what we are doing is working,” she says. “We constantly modify plans for better results.”

It pays off, too. Last year the company received 216 green awards from third-party organizations.

Consider this: In 2010, the environmental investment made by CRH totaled $67 million. Ten percent of the investment went toward reduction of air emissions; 5 percent toward restoration, landscaping and location upgrades; 9 percent toward reduction of water use; 24 percent toward waste reduction and management; 4 percent toward energy reduction and process optimization; 13 percent toward increased alternative materials and fuel use; and 35 percent toward monitoring and licensing environmental practices.

|

|

| Ware works on one of her many R&D projects. |

Walking the walk

At long last, when Ware goes home at the end of the day – or, rather, exits her home office in an effort to commute as little as possible – she delivers on her promise to Mother Earth in her personal life.

“When I walk through a tradeshow, I shiver seeing greenwash claims,” she says. “Similarly, I tremble at the sight of a neighborhood trash can full of plastic bottles or out-of-season fruit in the grocery store.” She recognizes consumers don’t spend their days reading environmental reports, but she knows exactly how much her daily habits impact the environment.

“I can’t just talk the talk; I have to walk the walk,” she adds. Ware hopes that the lessons she teaches in the office will travel home with her coworkers, too. Bonsal employees now turn their lights off when they leave the office, and recycling bins are at every location. Other key initiatives include video conferencing and a 20 percent reduction in company travel.

“The other day, one of our sales guys told me that he bought a hybrid as his personal vehicle and that he wouldn’t have considered it if he hadn’t heard the facts and figures I presented at our last Annual Meeting,” Ware says.

It’s all in a day’s work for a sustainability director.

| Case Study |

|

Functionally, the new 11,000-square-foot plaza in Milwaukee’s Garden District serves as a farmer’s market. Symbolically, it’s the beginning of a much larger green movement in an evolving section of the city. Completed this summer, the farmer’s market really began three years ago, when Bryan Simon, owner of Simon Landscape Co. Inc., started Energy Exchange. The nonprofit educates the public about rainwater management and other green topics. Simon’s vision included transforming a one-mile stretch of vacant or decaying spaces into a showcase of better management techniques in a city prone to overflowing storm sewers. An alderman championed Simon’s idea and expanded it with a resolution to create a 3.5-mile Green Corridor. Water-friendly upgrades, including permeable paving and bioswales, are popping up along the corridor, which also will serve as a testing ground for green technologies such as solar-powered signage and LED lighting. Simon’s own on-the-ground efforts started with a community garden on one end of the corridor with an adjacent farmer’s market. The farmer’s market features 66 10- X 10-foot stalls created using CalStar pavers in the autumn blend, laid in a basketweave pattern. Each booth is bordered by an eight-inch, dark gray soldier course. CalStar pavers in the tumbled natural color, arranged in a 90-degree herringbone pattern, create the eight-foot-wide aisles. Finally, the entire plaza is ringed by another dark gray soldier course. “I was looking for a way to make our farmer’s market unique and attract vendors and people,” says Simon of his decision to make the pavers an integral part of the design. The booth layouts forgo any jockeying for position by vendors, provide clear delineation for patrons and provide aesthetic interest even when the vast space is not in use. It took a crew of eight to 10 installers three weeks to place the nearly 65,000 pavers. In keeping with the corridor’s water management goals, all water that falls on the plaza remains. The space is designed to direct water flow to one end, where it is captured and stored. In the future, the water will be recirculated through a planned water feature and also pumped for use in the community garden. For the vehicular loading area, still under construction at the east end, Simon plans to install a four-foot strip of CalStar permeable pavers sandwiched between two, three-foot concrete bands. The market, which also can be used for other community and private events, will connect to the garden via brick walkways that will meander through a plaza-wide pergola. Along with aesthetics, the CalStar pavers add to the Corridor’s sustainability story. The pavers are made using CalStar’s proprietary manufacturing process that incorporates 40 percent local recycled material (fly ash, a byproduct from power plants) as the binder, which avoids the energy-intensive kiln firing required for clay pavers and the use of Portland cement contained in concrete pavers. This results in 85 percent less carbon emitted, and up to 85 percent less energy used for manufacturing. For this project, the manufacturer calculates that using 64,935 CalStar pavers, instead of traditional clay or concrete pavers, prevented nearly 25 tons of CO2 from being emitted, saved 32.5 million BTU of energy, and diverted 69 tons of waste from the landfill. For more information, visit www.calstarproducts.com. |

| Green Education |

So it stands to reason that teaching green construction techniques to today’s students also bodes well for the future of construction. That future will center on using sustainable materials within projects with a role to play in protecting the planet. The Artist’s Backyard is a joint project between N.C. State University’s departments of Landscape Architecture and University Housing. It’s a plaza and rain garden between two older dormitories, Owen and Turlington Halls. It uses a combination of StormPave permeable pavers from Pine Hall Brick, along with materials that were recycled from a building demolition. New benches anchor a gathering spot where students visit with each other, read a book or text their friends. Andrew Fox, an assistant professor at the NCSU College of Design, says The Artists Backyard is an outgrowth of last year’s renovation of Syme Hall on East Campus. Fox pursued a $20,000 teaching grant through the university to lead his students through a design-build exercise to improve the Syme Hall site from a muddy mess to a beautiful rain garden.

Before The Artist’s Backyard was built, surging stormwater would carry leaves and other debris across the existing concrete sidewalk. The solution is to use Low Impact Development design techniques to slow, capture and clean stormwater on site. Cisterns and the permeable paver installation re-direct stormwater into the rain garden and the ground, effectively filtering it and preventing erosion. Nine days after the installation was complete, Mother Nature handed the college students a pop quiz. Thunderstorms rolled across central North Carolina and dropped 4.69 inches of rain, amounting to a 100-year flood. “The surface water drained into the rain garden and it was dry, no puddling,” says Fox. “The rain garden had handled that huge pulse of rain water. After four hours, the test wells were slowly infiltrating and the water was not standing.” |

Farmer’s Market Plaza and Green Corridor bring rainwater management to Milwaukee

Farmer’s Market Plaza and Green Corridor bring rainwater management to Milwaukee The success of that project prompted Dr. Tim Luckadoo, associate vice chancellor for student affairs, who oversees housing on campus, to talk with Fox about additional projects. Those discussions turned into $175,000 in funding and a five-year plan to improve the landscapes around several N.C. State residence halls.

The success of that project prompted Dr. Tim Luckadoo, associate vice chancellor for student affairs, who oversees housing on campus, to talk with Fox about additional projects. Those discussions turned into $175,000 in funding and a five-year plan to improve the landscapes around several N.C. State residence halls.